Carsten Timmermann is a historian of biomedicine and Director of the Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University of Manchester. He has published on the history of cancer research and therapy, cardiovascular research (especially the concept of the risk factor) and a range of other issues in the history of modern medicine.

For more on his past and current work: Carsten Timmermann Research Profile

Your work on the history of cancer has investigated the emergence of ‘quality of life’ as a treatment outcome. Why is this of particular relevance currently?

Wikimedia Commons, licence CC BY-2.0.

Retrieved 21 March 2024, from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:King_George_VI_(15801734009).jpg

In February 2024, Buckingham Palace announced that King Charles had been diagnosed with and was receiving treatment for cancer. This announcement was remarkable in several regards, not least in that one of the central lines of the press release was that the king “remains wholly positive about his treatment”. A similar update has followed in recent weeks, with the announcement that the Princess of Wales is also undergoing cancer treatment. In this, she shared with the public how she has been coping amidst the news.

Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of this news, from a historical perspective, is the disclosing of a cancer diagnosis to the public. Only a few decades earlier it would have been unthinkable to speak about a monarch’s diagnosis so openly. The illness and death of King Charles’s grandfather, King George VI, from lung cancer in 1952 is a case in point. However, more subtle – yet distinct – is the emphasis on quality of life, both during and after treatment.

Such an emphasis on quality of life is not something we would have seen in discussions around cancer before the 1970s. Cancer was a taboo, and was associated with death. Accordingly, the conceptual space for concerns about quality of life in and after treatment was very limited. You either died or you survived.

Today, according to the charity Cancer Research UK, more than half of all patients diagnosed with cancer in the UK can expect to survive their diagnosis for 5 years or longer – a key measure of success. This is a remarkable improvement compared with the preceding decades. In 1970, only around a quarter of patients survived the initial five years following a diagnosis.

The causes of this improvement are manyfold and complex. These include improved diagnostics and treatment methods, and better treatment facilities. But this is not the focus of this piece. As a historian, I am interested in the shift of emphasis in cancer treatment’s focus: from securing survival to maintaining quality of life. This new focus also brought with it a difficult question: how to quantify improvements in quality of life? This was necessary if it was to be assessed as an outcome measure in clinical trials.

How did you first become interested in quality of life measurement in the history of cancer?

A history of lung cancer:

The recalcitrant disease. Springer.

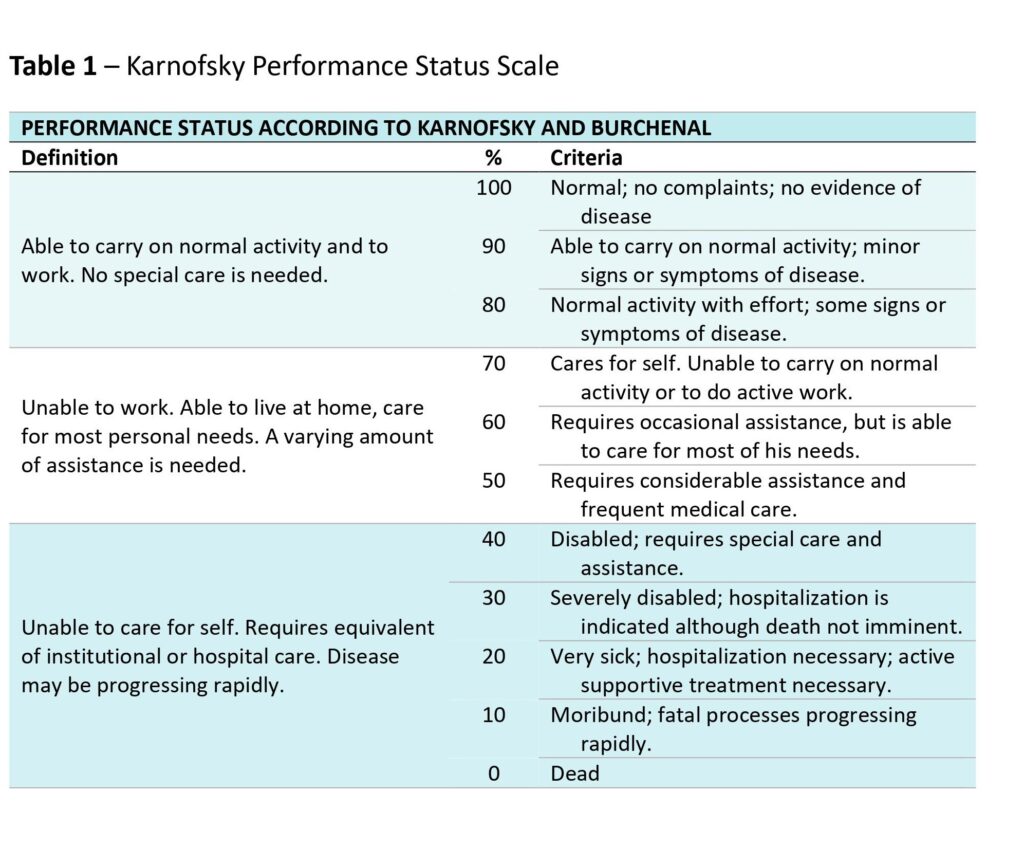

I initially became curious about this as part of my research on the history of lung cancer. In the early phases of research for my book’s chapters on clinical trials, I came across references to the Karnofsky Performance Scale, which appeared to be employed as a tool for measuring quality of life.

This simple scale was named after one of its inventors, the pioneer of cancer chemotherapy David Karnofsky. He had developed it in the 1940s at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Institute in New York City, together with his colleague Joseph Burchenal.

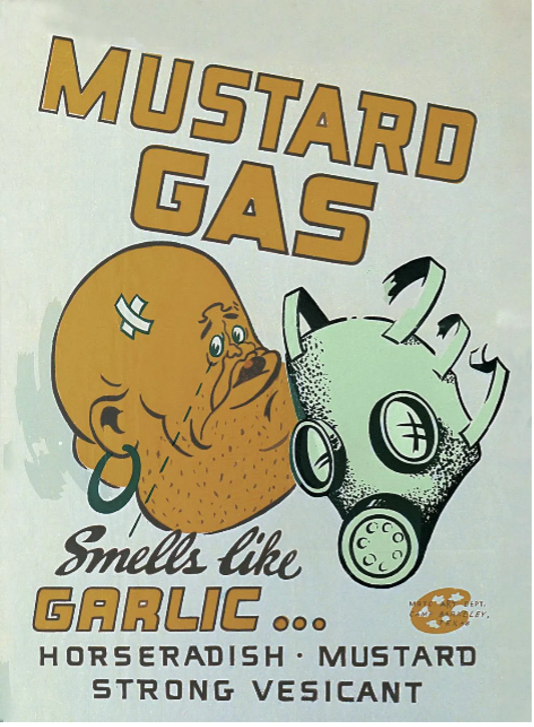

II-era poster. Otis Historical

Archives, National Museum of

Health and Medicine.

The context of the scale’s development had been for a trial of one of the first potential cancer chemotherapy substances: nitrogen mustard. Used in the war as a nerve agent, nitrogen mustard was an unspecific and incredibly toxic substance. But cytotoxic chemotherapy at this stage was an intervention of last resort – it was assumed that anything with the potential to kill a specific cancer would also nearly kill the patient. After all, there was not much that differentiated the cancerous cells from healthy cells in the body.

.

.

.

.

So was this as it appeared on first inspection? Were there any discrepancies between how this scale was established and what it went on to measure?

When I looked more closely at what Karnofsky and Burchenal had in mind when they developed the scale, I realised that quality of life was not mentioned.

Karnofsky and Burchenal had set out to measure three components to assess the impact of an injection of nitrogen mustard on patients. These were:

- Patients’ immediate objective improvement (OI). OI measures included any decrease in the size of the lung lesions, reductions in the volume of fluid in the chest, shrinking metastases, etc.

- Patients’ subjective improvement (SI). SI obviously, and by contrast to OI, depended on what patients reported. Did they feel better? Did they regain strength? How was their appetite? Were symptoms such as pain, cough, shortness of breath or headaches affected?

- Patients’ performance status: how far were they able to carry on with their daily activities unassisted? That is, how dependent were they on help?

The use of the nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of

carcinoma. With particular reference to bronchogenic carcinoma.

Cancer. 1948;1(4):634–656.

Intriguingly, Karnofsky and Burchenal’s scale was in fact intended to measure this final component – patients’ performance status. It was performance status therefore that later came to be known as the Karnofsky Performance Scale, or just the Karnofsky scale.

Yet Karnofsky and Burchenal had never explicitly referred to quality of life in any of their three assessment tools. And certainly not under performance status – if they had made reference to quality of life, this would probably have fallen under the category of ‘subjective improvement’.

I was intrigued. How and why was the Karnofsky scale reinterpreted as a measurement of quality of life, and when did quality of life become a concern for organisers of cancer trials?

Could you explain a little more about interest in quality of life at the time? Was this specific just to cancer?

Quality of life was a new concept in the 1970s, not only in medicine but also in other areas. Nobody was quite sure where the term had originated, but it was clear that its emergence was linked to some of the social shifts in Europe and America in the 1960s, to growing environmental concerns, and to questions of the time around limits to progress.

Especially relevant to quality of life becoming a common theme for clinical attention was medicine’s changing model around this time. The field had shifted from a paternalistic model, to instead placing a greater focus on patient autonomy. How well patients were individually and personally impacted by any cancer treatments was therefore an important priority.

What else was going on in the clinical realm at this time?

Chemotherapy had begun advancing towards its status as we know it today, as standard treatment for many forms of cancer. And the remissions it made possible – until this point unheard of – began to become long enough in duration to think of chemotherapy as curative. This brought with it necessary attention to the toxic, longer term effects of harsh chemotherapeutic treatments.

This increased use of chemotherapy also brought with it the rise of medical oncology as a discipline. The field went from relatively marginal, in the 1960s, to firmly established by the 1970s.

Sydenham (1967). Nursing Times: 28 July 1967.

Meanwhile, previously overlooked spiritual dimensions of cancer end-of-life care were brought to the fore through the hospice movement. Palliative care was no longer just about relief of symptoms from terminal illness – there was an added emphasis placed on ensuring dignified deaths.

.

.

.

.

So why did the Karnofsky scale continue to be used to measure quality of life? Was this accidental?

It was in fact widely agreed at the time that performance scales acted as poor, unreliable instruments for measuring quality of life.

Concerns around the appropriateness of different approaches to measuring quality of life had grown, and indeed grew to the point of active discussion among the scientific community by the 1980s. More sophisticated questionnaires were developed in response, incorporating psychological factors and patient self-reports.

Yet in spite of such concerns, questions remained that mirror those very commonly seen today in research, clinical trials and clinical practice: how to adequately assess patients’ feelings and perceptions, while avoiding impracticality and inefficiency?

Karnofsky and Burchenal’s scale had – and continues to have – one very clear benefit in this regard. It remained quick, easy and intuitive to use in a clinical setting. It provided physicians with an efficient and relatively straightforward tool for standardised assessment, indicating (rather than accurately measuring) the rather elusive concept of quality of life.

What can we learn from this for ongoing questions about patient care, treatment and complex decision-making in cancer?

Quality of life concerns in cancer medicine are context-dependent. While a young patient might prioritise survival over quality of life, an elderly patient may order their priorities in reverse. Financial factors also enter calculations of costs versus benefits. As some cancers become manageable long-term conditions, quality of life and performance may require reassessment and more critical longer term re-thinking.

Yet, despite this, I suspect that simple scales will likely continue to play a role. But important questions remain about what constitutes true quality of life, and who is best placed to judge and decide on this. The answer will always be complex and personal.

Medicine must inevitably operationalise the issues through necessarily imperfect tools, in order to incorporate patient wellbeing into evidence and decisions. However, understanding the historical roots of current practices may lead to improved, more carefully considered solutions moving forwards.

.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorses those views or opinions.