This piece was co-written by guest authors Dr Marie Kotzur and Dr Floor Christie-de Jong.

Dr Marie Kotzur is a Research Associate in the School of Mental Health & Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow. She has a background in health psychology and behavioural science, and her work focuses on the prevention and early diagnosis of cancer through increased screening participation. Since joining the Institute of Health and Wellbeing in 2015, Dr Kotzur has worked on several projects to understand barriers to cancer screening participation and supporting people in using cancer screening services. She is a founding member of the Cancer Behaviour Research Group and passionate about reducing inequalities in preventive health care and cancer outcomes.

Dr Floor Christie-de Jong is a Senior Lecturer in Public Health for Medicine at the School of Medicine, University of Sunderland. She moved into academia after several years of clinical practice in adult mental health and smoking cessation with the UK’s National Health Service. She initially worked in the field of tobacco control and then focused on cancer screening.

Dr Christie-de Jong was awarded a Master of Public Health from the University of Liverpool, MSc in Clinical Psychology from the University of Groningen and PhD in Public Health by Lancaster University. She has national and international research and teaching experience, and previously worked for Newcastle University, the online MPH at the University of Liverpool, the University of Calgary-Qatar, and Prince Sultan University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Dr Christie-de Jong is an associate member of FUSE, the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, a member of the Mixed Methods International Research Association and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Public Health.

How can we support Muslim women to better engage with cancer screening?

Across the UK, there are three NHS cancer screening programmes to support earlier diagnosis. These are for bowel, breast and cervical cancer. However, they can only help people who use them when invited. While overall participation rates may seem high (bowel screening — 67% uptake; breast screening — 75% uptake; cervical screening — 69% uptake), only bowel and breast achieve the NHS participation targets. In addition, cervical screening use is declining. Of additional concern, cancer screening participation is lower in marginalised groups compared with the general population. This includes ethnic minorities and religious minorities.

To address this, we worked with Muslim women to co-design a faith-based intervention to encourage uptake of cancer screening in their communities.

Looking to past research success

We knew that researchers in the USA had previously collaborated with Muslim women to increase breast screening participation. This intervention had used a ‘community meeting’ format. This had highlighted how Islam supports the use of breast screening and, equally, can help women overcome barriers to using breast screening.

All 58 participants had not attended breast screening in the 2 years prior to the community meeting intervention. However, by one year after the intervention, 22 of 58 participants had attended for breast screening.

Our research aims

Building on this, our research aimed to create a similar faith-based community meeting intervention for Muslim women in the UK. This was with a focus on faith-based support, for breast, bowel and cervical screening.

To ensure as much relevance and engagement as possible, we invited Muslim women in Scotland to help us plan and test the community meeting model to be used.

Co-designing the community meeting content

This research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning that we had to design a community meeting format that could take place online. We worked with ten Muslim women from Glasgow to co-design this, over the course of four online co-design workshops.

The women shared their own experiences of cancer and screening, and advised us what information they would like provided in the community meeting’s content. They also helped us to prioritise the greatest existing barriers to participation in bowel, breast, or cervical screening amongst Muslim women. Similarly, they discussed how their faith could help to overcome such barriers.

The women highlighted the importance of including women’s stories of cancer and screening. They also stressed that we should have a medical professional in attendance, to answer any questions about the screening programmes.

We thought that the community meeting design would be more effective if run by peer educators. Peer educators are community members knowledgeable about an issue but not health professionals – they are able to use their standing in the community to advise and support others.

We therefore introduced the role of peer educators in the final co-design workshop. After practising leading a discussion group through roleplay, five women agreed to act as peer educators for the community meetings. At their request, we provided further training on group facilitation: the peer educator role would involve leading small group discussions for the meetings themselves.

Delivering the community meeting intervention

We ran our online community meeting with two groups of Scottish Muslim women: the first group had 8 participants; the second group had 10 participants. Participants were recruited from a local mosque, and from community organisations via subsequent ‘snowball’ sampling. None of the participants had worked with us previously. The respective meetings were conducted via Zoom.

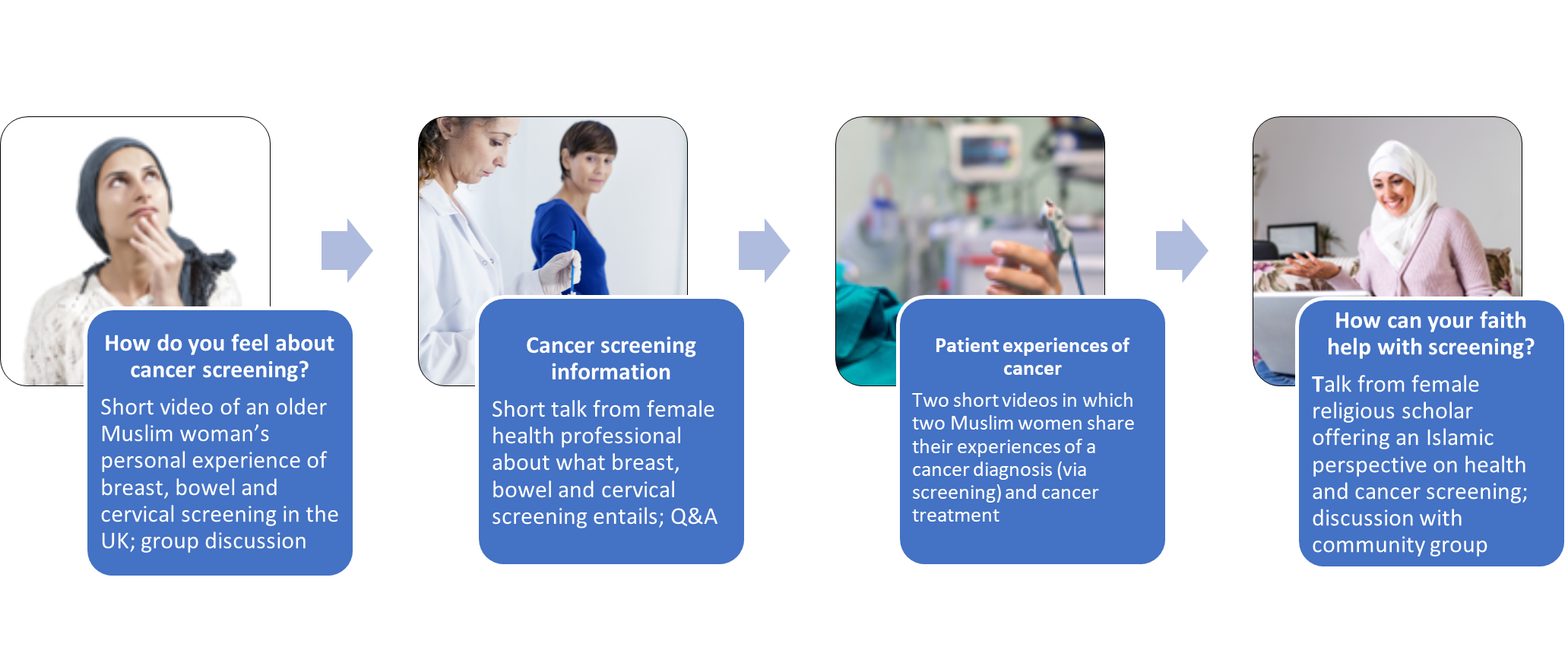

- After welcomes and introductions, attendees watched a five-minute video of an older Muslim woman sharing her experience of breast, bowel and cervical screening in the UK. Attendees were then divided into smaller breakout groups to discuss the video and their own screening experiences, led by peer educators.

- Next, a female GP gave a short talk on eligibility for the three NHS cancer screening programmes, the tests used, and what to expect as a patient. The women then had the opportunity to ask the GP any questions.

- Following a ten-minute break, attendees watched two more short videos. These were of two Muslim women’s experiences of screen-detected breast and bowel cancer, and of their subsequent treatment experiences.

- Finally, an Alimah, a female Muslim scholar, talked about how teachings from Islam support cancer screening and early diagnosis. She also discussed how Muslim faith can help women overcome potential barriers to cancer screening participation. Attendees then discussed their views of Islam and health with the Alimah. At the end of the meeting, we thanked everyone for their time.

Initial findings from our community meetings

A week after each of the two community meetings, we met again with each group. This was via two separate online focus groups, each two hours in length. We aimed to use these focus groups to learn what attendees thought of the community meeting content and format used, and how we might improve it.

Impactful video content

“I think the videos had, probably, the biggest impact”

Both groups appreciated the community meeting. Many said they found the content useful, and also interesting. They felt the four components made the meeting well-rounded. They particularly enjoyed the videos of women’s experiences: these highlighted the importance of Muslim faith as a source of comfort, and also encouraged them to participate in cancer screening.

Misunderstanding from non-Muslims

Some attendees shared that Islam encouraged them to look after their health. In this context, screening was therefore seen as good. Others voiced concern that non-Muslims may see Islam as a challenge to screening. They emphasised that Islam was an open religion and Muslim women were more likely to struggle with cultural barriers or a lack of awareness around screening, as opposed to any faith-based disagreement with screening.

Accessing trusted expertise

“It was like a precious time”

Attendees had liked how the meeting was run, and felt the two hours passed quickly. They particularly valued having access to expertise from the GP and the Alimah. The women said that both had presented information clearly. They also appreciated the opportunity to ask questions to the GP. They felt that the Alimah, as a community leader, could be a trusted source of information about health care for future community meeting attendees. She would encourage and support women who felt anxious about cancer screening or when waiting for test results.

Importance of language accessibility

“English is not the first language for them, so when they see it, they ignore it”

Attendees felt that a series of community meetings, together with more information material, would help Muslim women gain a better understanding of cancer and screening. They also highlighted the importance of linguistic cultural and religious relevance: using multiple languages, for both community meeting delivery and any information materials more generally, would ensure greater impact and increased accessibility.

Increasing impact through social connection

Finally, attendees said they would have liked to have been able to meet in person. They also thought that informal social components, such as sharing food, would contribute to the impact of the intervention.

What is next?

Following the community meeting intervention, some women decided to attend for cancer screening. Others took the step to book screening appointments themselves. However, this is insufficient information to confirm the initial effectiveness of the intervention. Assessing this effectiveness is our next goal.

We are delighted to have received funding from Cancer Research UK for a larger study. This will enable us to implement some of the improvements suggested in the post-meeting focus groups. We might involve translators in future community meetings, and we will compare the effectiveness of running the intervention in person versus online.

We will also compare the effectiveness of using the intervention with Muslim women in Scotland (where the meeting model was co-designed), versus with Muslim women in the North East of England. This will help us to ensure that any measured effectiveness remains relevant and impactful for Muslim women across the UK.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorses those views or opinions.

Leave a Reply