A friend of mine in her late 40s has just been diagnosed with breast cancer. Fortunately, she spotted it early and it sounds as if she is going to be OK. She’s lucky because we don’t offer breast screening to women under 50 in the UK unless they have a strong family history of breast cancer. Each year about a thousand women die from breast cancer before ever receiving an invitation for screening. Screening works in women in their 40’s but it is not recommended in most countries. With the publication of 25 years of follow-up from the “UK Age Trial”, a randomised controlled trial of screening in women aged 40-47, we review the arguments for and against screening and ask if it is time to reconsider.

What does the new publication show?

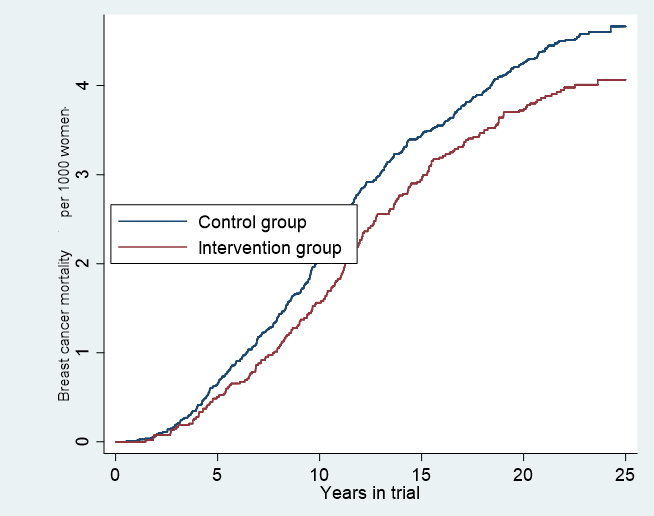

160,000 women aged 39-42 were randomised between 1990 and 1997. Two-thirds were “controls” and one third were invited to a yearly mammographic screening until they turned 47 or 48. Just under 70% of those invited for screening were screened in each round, and just over 80% were screened at least once. The women were followed for an average of 23 years. There was a statistically significant 25% reduction in deaths from breast cancer within 10 years of randomisation among women invited for screening. Among women screened regularly, it was estimated that screening reduced their chances of dying from breast cancer within 10 years of starting screening by about a third (34%). In absolute terms, about one woman avoided dying from breast cancer in her 40s or early 50s for every 1000 screened. On average those women will probably live for an extra 35 years.

With up to 27 years of follow-up, the new publication shows that although there is no further reduction in mortality (from breast cancers diagnosed during the intervention period) more than 10 years after randomisation, neither is there any reduction in the absolute benefit of screening on breast cancer mortality. Studying deaths from breast cancer diagnosed before the first routine NHS breast cancer screening invitation (at aged 50-52), but occurring at least 10 years after diagnosis the rate in the control arm was 19.2 per 100,000 women-years compared with 18.9 in the intervention arm.

There is no free lunch. Not only is mammography expensive for the NHS, but there are also downsides of participating in screening. It is estimated that the current screening programme costs about £160 million each year to offer seven screens over 20 years to women aged 50-70. Thus, offering a further 7 screens to women int heir 40s could double the costs – another £160 million.

The most concerning harm of breast cancer screening is over-diagnosis – diagnosing a cancer during screening that would not have been diagnosed without screening. The good news for starting screening earlier is that this trial showed that it made no difference to over-diagnosis. Although there was a small increase (9% more) in breast cancer diagnosed in the group invited for screening during the intervention period, this excess completely disappeared once women were invited for routine breast screening (at age 50-52). Beginning screening earlier does not increase a woman’s chance of being overdiagnosed.

The other harm of breast screening is caused by having a false-positive screen (i.e. being told that the screen is positive but learning, after further evaluation, that it is not cancer), which will lead to further medical investigations and often cause anxiety. In this study, 5% (1 in 20) of first screens were false positives and 3% of subsequent screens were. Since screening was offered annually, over the course of the study, 18% (nearly 1 in 5) of screened women had at least one false-positive result.

What do others say?

In some countries, such as the USA, most women begin screening int heir 40’s. In others, such as The Netherlands, screening under the age of 50 is rare. Recommendations regarding breast cancer screening in women aged 40-49 are also variable. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends:

The decision to start screening mammography in women prior to age 50 years should be an individual one. Women who place a higher value on the potential benefit than the potential harms may choose to begin biennial screening between the ages of 40 and 49 years.

- While screening mammography in women aged 40 to 49 years may reduce the risk for breast cancer death, the number of deaths averted is smaller than that in older women and the number of false-positive results and unnecessary biopsies is larger. The balance of benefits and harms is likely to improve as women move from their early to late 40s.

Whereas the American Cancer Society recommends:

Women with an average risk of breast cancer should undergo regular screening mammography starting at age 45 years (strong recommendation). …. Women should have the opportunity to begin annual screening between the ages of 40 and 44 years (qualified recommendation).

The European Commission makes the following recommendations regarding breast cancer screening:

Aged 40-44: no screening

Aged 45-49: screening every 2 or 3 years

Whereas breast cancer screening has never been routine in women aged under 50 in the UK, there has been some variation in policy over the years. In 2007, the then Prime Minister, Gordon Brown announced in the Cancer Reform Strategy that:

To improve and expand cancer screening, the government will:

- Extend breast screening to nine screening rounds between 47 and 73 years, with a guarantee that women will have their first screening before the age of 50.

That extension never happened. Instead of a randomised trial, AgeX was initiated in which women were randomly invited either from 50-73 or from 47-70. The justification for the trial at the time was that the screening programme did not have sufficient capacity to add two extra screens (one at 47 and one at 73) and so the roll-out of the age-extension should start with one additional screen. It is now clear that women who are not part of the AgeX trial are not eligible for breast screening until they turn 50 (unless they have a very high risk of developing breast cancer). Approximately a third of women in England are invited for breast screening aged 47-49.

What next?

The NHS Long Term Plan includes:

“By 2028 the Plan commits to dramatically improving cancer survival, partly by increasing the proportion of cancers diagnosed early, from a half to three quarters.”

Overall, about 12% of women who get breast cancer aged under 45 die within 5 years compared to about 8% of those aged 45-64. Since, stage-specific survival is similar at different ages, the worse survival of younger women is mainly due to their cancers being diagnosed later. In 2003, I argued that breast screening should start at age 47 years. With this new evidence, is it time to reconsider extending the breast screening programme? Should all women be given the choice to begin breast cancer screening before they turn 48? In the UK that could be achieved by lowering the age of first screening to 45 so that women would receive their first invitation between age 45 and 47.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.