After months of eager anticipation, the results from the English HPV implementation pilot have been published. Compared to current screening HPV testing detected 50% more CIN2+, 40% more CIN3+ and 30% more cancer in the first round of screening. For the first time, this has been shown not just in a randomised controlled trial of tens of thousands of women but within a pilot implementation involving over a million women.

A real-world study

The pilot study was carried out in a real-world setting. During this pilot, six NHS screening laboratories continued to offer cytology screening, but converted about a third of their screening operations to HPV testing. Most women participating in the pilot would have been screened previously within the cervical screening programme. Those early screens would have been tested by cytology. Women attending screening will not notice any difference in the way the test Is taken. The difference is the way the sample is tested in the laboratory and in their management thereafter.

In the first round almost 1.1 million women had conventional screening and 440,000 were screened by HPV testing. Those screened by HPV testing had nearly 50% more high-grade “pre-cancer” (CIN2+) detected and 32% more cancers. This benefit was seen across the entire age span.

Increased demand for colposcopy services

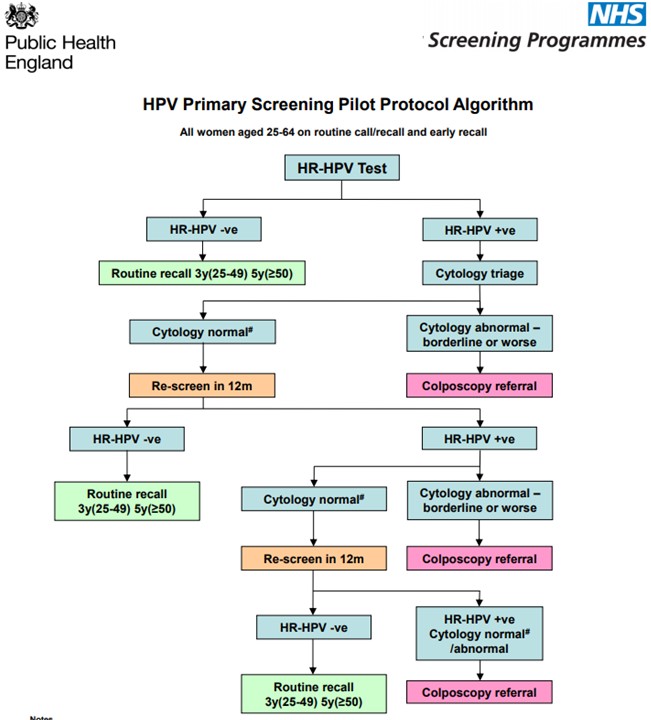

As is often the case with new screening tests, the increased ability to detect disease (better sensitivity) comes at a price – more women without disease have a positive test result (the test is less specific). The pilot showed that about four times as many women have a positive HPV screening test than was the case with cytology. This was as expected. Samples that are HPV positive are retested with cytology and only those women who also have abnormal cytology are referred to colposcopy. Women who are HPV positive but have normal cytology are unlikely to have disease present but are at somewhat increased risk of developing disease in the future. These women are screened annually to see whether the HPV infection clears spontaneously (as it does in about half of these women) or whether they need colposcopy. The pilot found that with this management of HPV positive women the demand for colposcopy was 77% higher than in the current programme. One of the main concerns for screening programme managers has been coping with the increase in demand for colposcopy arising from the introduction of the more sensitive test. However, this increase is likely to be restricted to the first round of HPV testing and hence be temporary. The paper did not report any difficulties in delivering the extra colposcopy within the pilot.

Although the relative increase in the colposcopy workload was similar at all ages, in absolute terms 46% of all colposcopies in the first round were in women aged 24-29. When HPV primary screening is rolled out nationally at the end of 2019, these young women will have had the opportunity to have been vaccinated against HPV and therefore many fewer should test positive and be referred to colposcopy.

Should screening intervals be extended?

Since HPV testing is more sensitive than cytology, it was expected that more disease would be diagnosed in the first round of screening in the pilot. Picking up and treating more disease within the first round should lead to less disease in the second round (three years later in women aged 25-49). Results from the pilot confirm this.

Early results from the second round (based on the first 110,000 women to be screened in round 2 all of whom were under age 50) show that CIN3+ was detected on the second round in fewer than 1 in 1000 (0.1%) among those initially tested with HPV compared to 5 in 1000 (0.5%) among those initially tested with cervical cytology. Further, there were no screen-detected cancers is 33,506 women tested initially by HPV compared with 15 in 77,017 initially screened by cytology. In the coming months and years more data will accumulate, including data on women older than 50 years and on cancers that were not diagnosed on screening. Although there will certainly be more cancers in women in the HPV arm, we see no reason why those results will not show the same patterns observed already.

Although the screening-interval within the pilot was three years (in women aged 25-49), the very low rate of CIN3+ among those tested with HPV confirms the suggestion that it is safe to extend screening intervals to at least 5 years even when HPV testing is done in hundreds of thousands of women.

Why are these results so important?

This very large-scale pilot clearly demonstrates that it is possible to introduce HPV primary screening nationally and to achieve the anticipated gains in reduced cancer incidence.

The results from this study will be extremely influential in defining primary HPV screening programme guidelines in England. This is a very exciting time for cervical cancer control. HPV-based screening and HPV vaccination should result in substantial decreases in cervical cancer incidence. What we had previously predicted based on small but carefully run research studies is looking to be a reality with our national health system.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.

Further research is needed to understand why women are reluctant to have extended screening intervals. There are no data about why women are unwilling to have extended intervals for primary HPV testing, but in research on Pap smears, women were also reluctant to have extended screening intervals; 69% of women reported that they would continue to receive annual screening, even if advised it was not required

Now Cobas Testing is available which is reliable than Pap and also save time and money.

Pingback: How much should we be willing to spend to introduce a public health intervention sooner? – Cancer Prevention Group Blog

Pingback: 10 must read papers from the last year – Cancer Prevention Group Blog