This post was written by Dr Jo Waller & Dr Laura Marlow. Jo is a reader in cancer behavioural science & has a particular interest in cervical cancer prevention and has published extensively on barriers to screening uptake, the psychological impact of HPV testing, and attitudes to HPV vaccination. Laura is a research psychologist in the behavioural science team within the Cancer Prevention group, where she has a particular interest in ethnic inequalities and has also worked on understanding cancer fear, fatalism and stigma.

Our colleagues Milena Falcaro, Peter Sasieni and others have recently published the exciting finding that HPV vaccination has reduced cervical cancer incidence by almost 90% in England. We celebrated this by publishing an interview with Margaret Stanley who talks about her part in the story of HPV vaccine development. In her interview, she touches on the importance of the work that went on behind the scenes, while the HPV vaccination programme was being planned. Part of this work was carried out by behavioural scientists. We thought this would be a good moment to reflect on our 15 years of behavioural science research in the field of HPV vaccination.

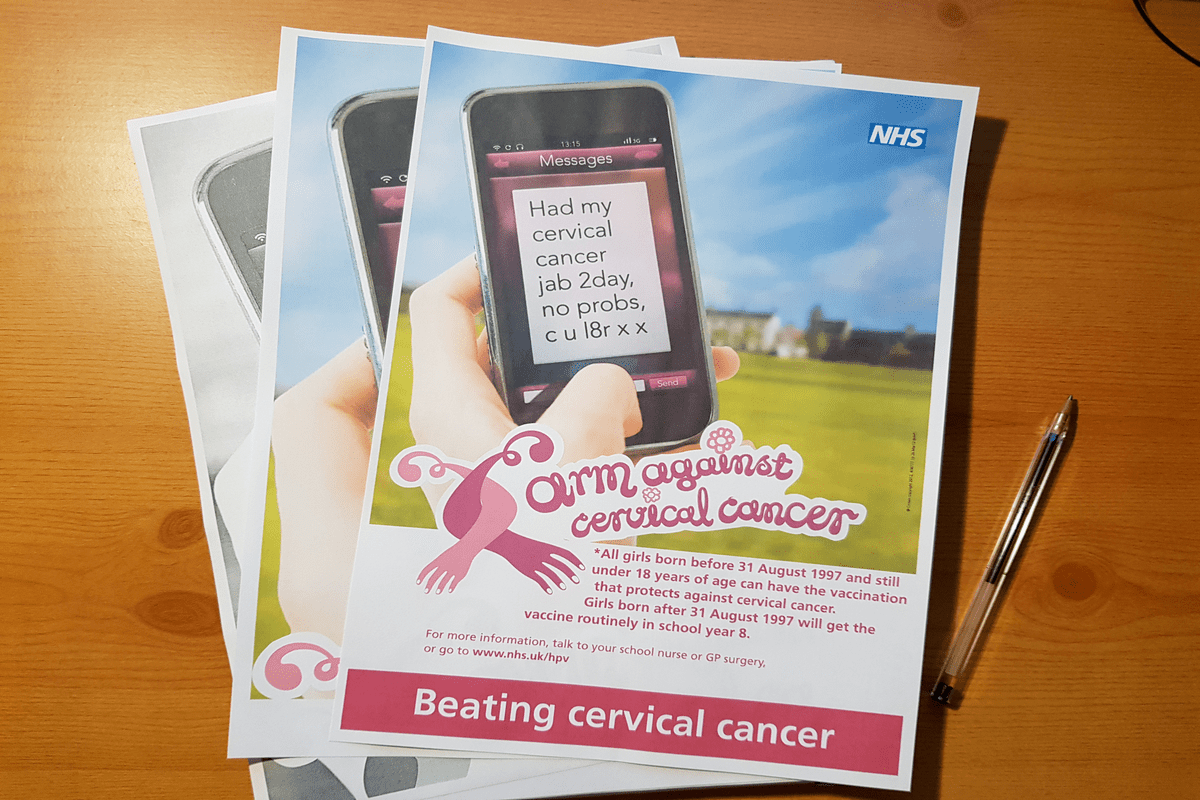

Back in 2005, we began doing research to assess parental attitudes to HPV vaccination. Greg Zimet had started doing this kind of work in the US, finding that the sexually transmitted nature of HPV might pose a barrier to acceptance of a vaccine for adolescents. The issue was compounded by low levels of public awareness of HPV at the time and a lack of understanding about how a virus could cause cancer. It was clear that the success of any HPV vaccination programme would depend on these issues being understood and addressed to ensure high levels of uptake. Working with the late Jane Wardle, we began a programme of research, beginning with a qualitative focus group study of mothers of 8-14-year-old girls. While there was great enthusiasm for a vaccine to prevent cancer, concerns were expressed about vaccinating very young girls against a sexually transmitted infection (STI), about whether this was even necessary and how difficult it would be to discuss a vaccine against an STI with children. There were also questions about the potential of an HPV vaccine to affect sexual behaviour – something the media often chose to focus on when discussing the vaccine. Although the vaccine was licenced for use from age 9 years, our work contributed to the evidence base on which the decision to offer vaccination to 12–13-year-olds in England, rather than to younger children, was made. Along with other findings, our work supported the benefits of launching a campaign focused on the prevention of cervical cancer rather than a vaccination against an STI and the ‘arm against cervical cancer’ campaign was launched by the NHS when the first cohorts were offered the vaccine.

The issue of the HPV vaccine potentially affecting sexual behaviour was picked up by our colleague Alice Forster in her doctoral research. There were two hypotheses for how this might be possible. The first was that having the HPV vaccine would give adolescents a ‘green light’ to become sexually active, conveying an implicit message that they were now old enough to need protection from an STI. The second was a risk compensation hypothesis – that the protection afforded by the vaccine might encourage greater risk-taking in other behaviours i.e. sexual activity. Both hypotheses were rejected, providing reassuring evidence with which to counter parental concerns about this issue.

Throughout this work understanding inequalities has been at the forefront of our study designs. While school-based vaccination programmes can help minimise inequalities in uptake, these are not fully eradicated, as highlighted by our recent collaboration with the Institute of Child Health using Millennium Cohort Data. In particular, it became clear early on that acceptance was likely to be lower among ethnic minority parents and a review that pulled together all this early work suggested this was in part due to a magnification of concerns about issues related to sexual behaviour and the need for a vaccine against an STI, but there were also culturally specific attitudes related to religious beliefs and taboos surrounding STIs. Some of these issues are touched on in a previous blog, where Rose Brade describes her own experiences with vaccine hesitancy as a black British woman whose mother objected to her having the HPV vaccine when it was offered to her in 2008.

More recently, we explored the acceptability of HPV vaccination for boys, ahead of the roll-out of the gender-neutral programme in the UK, something our late colleague Anne Szarewski had been calling for since 2007. Even in 2019, more than a decade after the introduction of the girls’ vaccination programme and 7 years after the introduction of HPV testing for triage in the cervical screening programme, awareness of HPV remained low; only just over half of the parents surveyed had heard of it. Poor knowledge of HPV was associated with a lower willingness to accept the vaccine offer, and parents of boys had lower intentions to vaccinate than parents of girls. Reassuringly, although nearly a third of parents of boys were unsure about their vaccine decision, only 11% had decided not to vaccinate.

The HPV vaccination programme in the UK has been highly effective and we are proud to have played a part in ensuring its success by better understanding uptake behaviour and how to offer the vaccine in order to maximise uptake. In the UK, it will be important to continue to monitor and address inequalities in uptake and to ensure that we vaccinate those who have missed out due to the Coronavirus pandemic. Worldwide, the challenge is much bigger. As well as wide variations in vaccine roll-out across the globe, country-specific barriers to uptake like those experienced in Japan must be addressed, with behavioural science playing a key role. To achieve the WHO target of fully vaccinating 90% of girls by age 15, as part of the ambition to eliminate cervical cancer globally, huge efforts are needed to ensure those in low- and middle-income countries, where the burden of HPV-related disease is greatest, can reap the rewards of this fantastically effective public health intervention.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.

Share this Page