This blog was written by: Karen Manton, Simon Milner, Jill Barker, Kate Sykes:

Karen: I have been a Mental Health Advocate for several years. I began sharing my lived experience with the students at Teesside University almost three years ago as I am passionate about helping others.

I was involved in the PECCS study as an ‘expert by lived experience’.

Simon: I live in Botton Village. I work as a paid life of opportunity reviewer and help improve support for people living in our communities. I also work as a volunteer in the Botton cafe and farm.

I was also involved in the PECCS study as an ‘expert by lived experience’.

Jill: I am co-lead for this study with Kate. I am a mental health practitioner and academic. I am keen to ensure that health services are accessible to everyone, ensuring those who experience health inequalities are provided with relevant reasonable adjustments to support them.

Kate: I am co-lead for this study with Jill. I am a researcher and lecturer. I want to make healthcare services accessible to people, who would normally struggle to. My email is kate.sykes@northumbria.ac.uk if you want to ask questions about the study.

About the study

This blog is based on the experiences of two experts by lived experiences, Karen and Simon, who were involved in the Person Centred Cancer Screening (PECCS) study. A summary of the study (which is now finished) is below:

Aim of the study:

To find out what influences the decisions of people with severe mental illness and people with learning disabilities to take part in cancer screening programmes.

Summary of study:

1) We completed a systematic review to look at what is already known about the barriers and facilitators to people with severe mental illness in completing cervical, breast and colorectal screening;

2) We then did interviews with people with Bipolar Disorder. This was because there was not a lot of information in the systematic review from people with Bipolar Disorder about completing screening, and;

3) We then combined and synthesised the information from steps 1 and 2, with data which focused on people with learning disabilities. This is called triangulation. We did this to generate recommendations on how we can improve cancer screening for people with severe mental illness and people with learning disabilities.

What was our approach to patient and public involvement?

We involved a total of 5 people with lived experiences; 3 people with severe mental illness, and 2 people with learning disabilities. Karen and Simon were part of this. The people with lived experiences were invited to be experts at different stages throughout the study. People with severe mental illness were involved from the beginning, and we involved people with learning disabilities to help with triangulation and making recommendations. Everyone was invited to be involved in all activities, and given a choice to be involved or not.

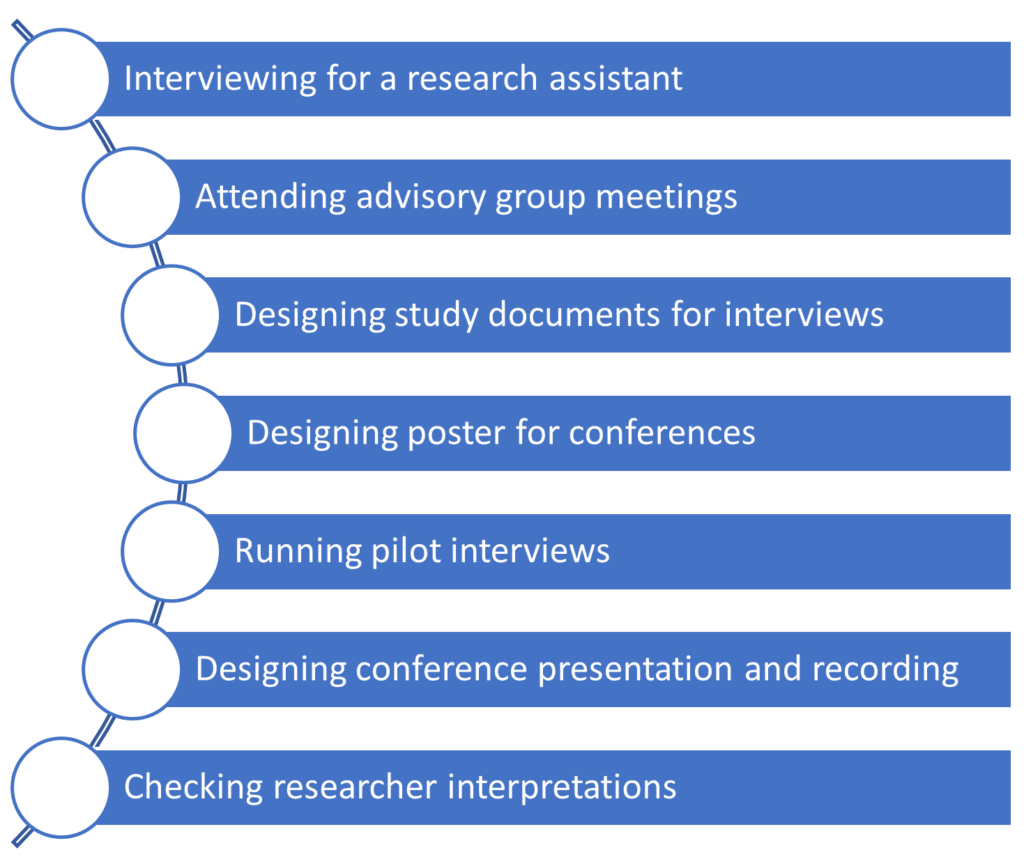

We embedded co-production and patient and public involvement from the outset and throughout the study. We found this a helpful approach for the study. This helped us develop strong working relationships from the outset and we became a team. It meant that everyone knew what had happened previously, and what the next steps of the study were. It provided consistency for the entire team as everyone knew each other. It also meant experts with lived experiences could be involved in a variety of activities if they wanted to, and the list of activities experts completed throughout the study is in Figure 1 below:

Were experts paid for their involvement?

Yes, experts were paid for their involvement. Experts were paid using the NIHR payment rates. The research team set Karen and Simon up as noncontractual members of staff with the university. This was the preferred option for most experts involved, Karen recalled a previous opportunity being asked if she would accept vouchers as payments. This was deemed not appropriate and not reflective of the precious time and input from experts.

Brief summary of research findings:

Here are the key points from the study.

- Systematic review: We analysed the data from 20 papers from across the world. Common barriers to attending screening included poor communication from healthcare staff, stigmatising attitudes, and accessibility problems such as no access to transportation. While, facilitators included social support from friends, family, and healthcare providers.

- Interviews: We completed 27 interviews with people with Bipolar Disorder, from 11 different location in the North East of England, 6 males and 21 females took part, ages ranged from 25-68 years. Some of the barriers for cervical and breast screening were lack of awareness of screening, travelling to appointments and pain during screening. Some of the barriers for colorectal screening were not knowing how to complete the kit and completing the kit at home. We are writing these findings up for publication.

- Triangulation: We found 50 barriers/facilitators for people with learning disability; 82 barriers/facilitators for people with severe mental illness; 22 overlapping barriers/facilitators meaning they are similar across the two groups. From these we made a list of 99 recommendations to make screening better. Example recommendation: 1) have a pre-invitation appointment with a doctor or nurse to talk about screening and what to do; 2) have more promotion of screening such as on the TV.

Karen’s and Simon’s experiences

Jill and Kate met with Karen and Simon at the end of the study and asked them a range of questions about their experiences of being experts by lived experiences as neither have been involved in research as an expert before. Both were provided with the questions beforehand so they could consider their response. Where possible direct quotes from Karen and Simon have been used and shared with their permission.

Why did Karen and Simon want to get involved?

Karen said that people with bipolar disorder can have a shorter life expectancy, but it isn’t because of their illness, it’s the contributory factors such as not looking after themselves. This means that some people won’t take part in cancer screening because they are not well. Karen said, “I wanted to let people know how to live a long and healthy life, and to go and get screening”. Similarly, Simon also said he wanted to be involved so people “don’t suffer if they didn’t go and get checked out”. Simon also shared his personal experiences of going through cancer treatment, so he wanted to turn a personal and difficult experience, into a positive for other people.

What things did Karen and Simon get involved in?

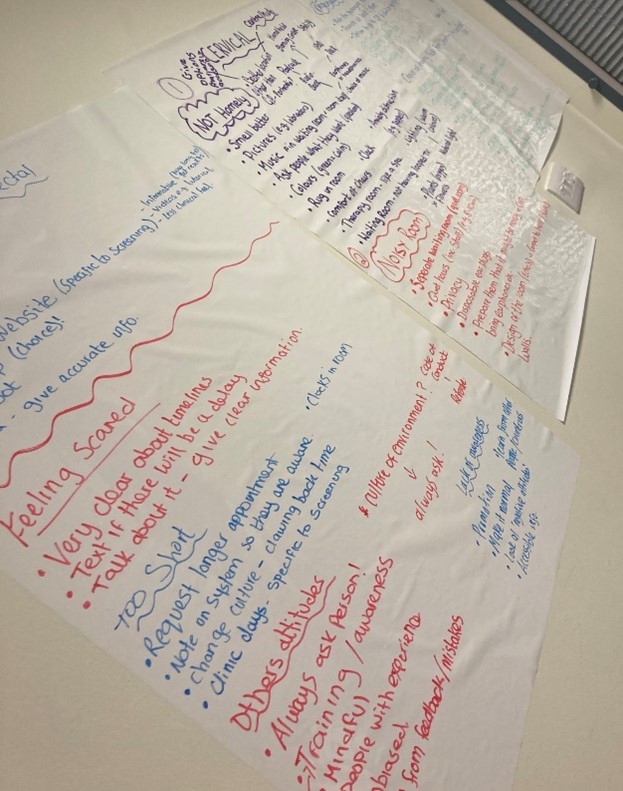

Karen and Simon have been involved in a range of activities (presented in Figure 1 at the beginning of the blog). Karen recalled talking about being on the interview panel for the research associate: “I felt really honoured that you asked me to be on those interviews. And I know what you said, Jill. I remember you saying it helped you to look through the interviews in a different lens. And I thought that was really, really nice.”. Karen also discussed how being part of the advisory group meetings made her feel visible to others “they’re all in offices or wherever they are, but they need to see that this is how it affects a person. You know, we’re not just talking about a statistic or a name”. Simon started being an expert half way through the project. Simon was involved in a piece of work called triangulation, along with Karen and another expert called Esther. Experts and the research team met face to face twice. The first time was to check the researcher’s interpretations of the findings from completing the initial triangulation. which was shared using pictures and the second meeting was to generate recommendations (picture 1 below). The recommendations that were made were focusing on making it easier for people to make a decision about going/completing screening, and then be supported in completing.

Experts also co-produced and presented a poster at the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) North East and North Cumbria (NENC) Inequalities Theme Event.

What was good about being an expert?

Multiple good points were documented:

- Continuous communication/updates: Karen said that she enjoyed being an expert through lived experience, especially the continued contact with the researchers; “I enjoyed the way you touched base all the time… I think there’s nothing worse than somebody getting in touch with you and they ask you, do you want to be involved in something and you’re all keen and excited and then you don’t hear anything and you think, well, fine, if it hasn’t come off , there’s a reason. But update me and that’s what I don’t like, to be just left in the dark”. Simon also agreed he was kept up to date with the support of Colin, (a member of staff from the Community Village where Simon lives) “I was definitely up to date with all the projects and things because Colin always told me what’s going on and things like that”. Both noted that meeting over the computer provided them with more flexibility. Both Karen and Simon said that they felt part of the research team.

- Project meetings: Karen also said she liked that we had smaller project meetings, outside of the advisory group meetings, this was useful to know what activities were coming next; “This is the part we’ve done and you’d go through it and this is where we’re up to now. So this is what we’re going to want from you next.”. She felt this was critical in ensuring co-production was embedded throughout the study. Simon reflected on Karen’s positive comments, he especially liked the face-to-face meetings.

Karen and Simon’s recommendations for researchers

- Limit the use of jargon: Simon said that in the advisory group meetings, some people used jargon; “I do sometimes think some of them were speaking a bit jargon, but I always asked Colin to try. And what’s it called? Translate it, translate it a bit”. From this, we think that the research team should challenge people using jargon, and make sure that meetings are “jargon free zone” so everyone can understand.

- Do not be scared: Karen said from her experiences some academics/researchers are frightened to contact service users thinking they are troubling them or because “they might be too busy”. However, Karen said that researchers should not be scared to ask people to be involved in their research because they want to help make changes: “Don’t fear us because there’s nothing to fear because I’m pretty sure the service users want those changes to happen. They’ll want their life to be made easier.”

- Include us, don’t exclude us: Karen said “We are there to represent people similar to ourselves, but it is important because if we don’t speak up and say how it could affect us, how are the professionals ever going to understand?” which highlights the importance of experts, as they can share their experiences that are unique to them to help professionals understand their health and lives. Simon also said that people with disabilities should be included because they won’t have their opinions heard “It’s kind of nice to include people with disability so……. they’re not like excluded from like from this because otherwise if they….don’t have their opinions voiced, then you nothing will happen really”. With this Simon also highlighted that people are not hard to reach because they do want their voices to be heard, they might just not have the opportunity to share them; “you know, you’re not hard to reach if you know where to look”

The views expressed are those of the authors. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorses those views or opinions.