A phase III multicentre trial of weekly induction chemotherapy followed by standard chemoradiation versus standard chemoradioation alone, in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer

Aim: To investigate whether an additional short course of chemotherapy, given on a weekly schedule immediately before standard chemoradiation, leads to an improvement in overall survival in women with locally advanced cervical cancer.

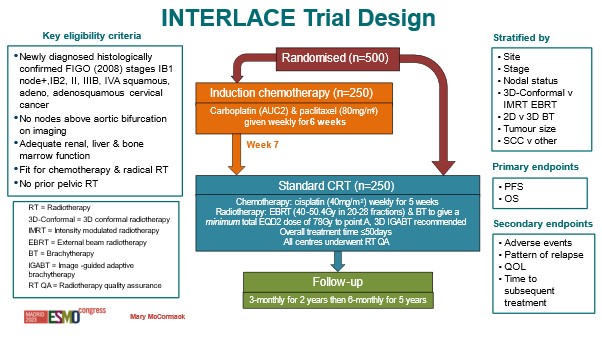

Treatment: Patients were randomised to receive either the current standard treatment of chemoradiation (cisplatin chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy) for 5 weeks, or 6 weeks of induction chemotherapy (comprised of carboplatin and paclitaxel) followed by standard chemoradiation.

Duration of recruitment: November 2012 to November 2022

Target sample size: 500

Outcome: Results from the INTERLACE trial show that giving cervical cancer patients a short course of chemotherapy before starting standard treatment cuts the risk of death, or the risk of the disease returning, by 35%.

We caught up with Dr Mary McCormack, the trial’s lead investigator, to ask her all about it.

This is a fantastic result, which could potentially reduce the numbers dying from locally advanced cervical cancer. Do you know how many women might be eligible for this new treatment regime each year, globally and in the UK?

Globally, in 2020 there were over 600,000 new cervical cancer cases diagnosed. 90% of those were from low- and middle-income countries, and approximately 70% of those were likely to have locally advanced disease and potentially be eligible for this additional treatment.

Here in the UK, we have about 3,500 new cervical cancer cases a year. At least half of those will have locally advanced disease – and therefore be potentially eligible. We need to remember that these are usually young women in their 30’s and 40’s often with young families.

How did you come up with the idea for the trial?

Well, back in the early 2000s, the use of cisplatin (as chemotherapy) alongside radiation was introduced. That was a big step forward: study results showed that adding chemotherapy to radiation improved overall survival and reduced the risk of the cancer returning.

But even with this, the disease recurred in up 40% of cases. So clearly there was an unmet need and room for improvement.

In 2003, a meta-analysis then looked at all past trials that had investigated delivering chemotherapy before radiation. These trials had mostly been conducted in the ‘90s.

Across the different trials, there was a great deal of heterogeneity. Different trial formats, different drugs, different schedules, and small numbers of patients. But what they did find was that the cycle length – i.e. cycles longer (or shorter) than the standard 14-day period – seemed to have an impact on the outcome. There was a suggestion that giving chemotherapy more frequently might actually be beneficial.

We therefore wondered if there might be scope to develop this further – to look at it with fresh eyes, building on what had already been done and see if we could make it better. We decided to use weekly chemotherapy and combined the two most active drugs in cervical cancer treatment.

Firstly, we did a phase II study, to see whether it was feasible to give this additional chemotherapy weekly for 6 weeks followed by the standard chemoRads. The study confirmed that this approach was indeed feasible.

Is that what was seen in the other trials you mentioned: that the gap was too long – that it did more harm than good?

The older trials in the meta-analysis didn’t look at the delay between chemotherapy and radiotherapy. I personally think that was one of the reasons why some of those trials failed.

Can you explain a little more about the weekly treatment for the trial?

We combined two drugs: carboplatin and paclitaxel. The latter was not available when the trials were done in the early 1990s. We gave 6 weeks of both drugs, and then in week 7 patients started the standard chemotherapy + radiation.

Based on this – and given what we’ve shown with INTERLACE – my takeaway is that the two key elements for improving outcomes are: weekly treatment, and elimination of the gap between finishing induction chemo and starting chemoradiation.

You ran the trial in the UK, Mexico, India, Italy and Brazil. That must have been a huge effort to coordinate and quality manage?

Yes, it was. Our team from UCL were wonderful at coordinating this. We also learned pretty early on that you needed to have a study champion in each of the different regions.

We recruited about 20% of our patients from Mexico. The investigator there, who has unfortunately since passed away, was very supportive of the trial. They had lots of patients and so she made it happen. We also recruited a small number of patients from two hospitals in India, working in partnership with the Kolkata Gynaecology Oncology group. Gynaecological oncologist Asima Mukhopadhyay (pictured above far right) led the study in India. The only real barrier to more extensive recruitment was a lack of funding.

We also worked as part of the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) – a collaboration of gynaecological cancer clinicians that meet twice a year. I went along to all their meetings for years at my own expense. There is no funding for attendance at such academic meetings, but I recognised the importance of promoting the institution and the trial. It was important to let people know this trial was still running, as there were other trials afoot at the same time and we didn’t want to be forgotten.

There were times when we wondered if we would ever complete recruitment. But we were determined to get the trial completed.

We also had challenges with our funding because the trial went on for so long. We had hoped to finish it in five years, and it ended up taking ten. So we had to justify – and defend – this to the funder.

There were definitely a lot of challenges and obstacles along the way, and it was by no means plain sailing.

How was your recruitment looking at the 5-year mark? Did you have half of your intended number of participants by this point?

No, we did not. The recruitment was very slow, a lot of which was because it took quite a while to get the trial sites open for recruitment. This is a known problem in the UK: getting sites open to participate in clinical trials is slow.

But we also had another couple of factors slowing recruitment efforts:

- One of the things we had mandated within the trial was prospective radiation quality assurance for the radiotherapy. But most (in fact, pretty much all) of the UK sites had never participated in a gynaecological cancer trial with prospective quality assurance in place for radiation. The National RTQA centre at Mount Vernon Hospital worked very closely with us to establish and oversee the programme.

- The second issue we had was with the standard dosing for radiation in the UK at the time. This was quite low (too low for the trial), so centres had to increase their dose in order to participate in the trial.

So, with all these things combined, it took quite a long time to get a sufficient number of centres open to recruitment. Things were going very well in 2019, but then the pandemic happened and recruitment was on hold for a number of months.

Were patients generally receptive to the idea of the treatment being offered (weekly chemotherapy followed by standard chemoradiation)?

Yes. That said, one major aspect that was off-putting for patients was the possibility of hair loss. There’s a risk of losing your hair with paclitaxel, although we do know from its widespread clinical use that scalp cooling can reduce the likelihood of complete alopecia.

We made a promotional video, featuring a specialist nurse and two patients talking about their experience on the trial. That was really important.

Going back to the trial’s international collaborations, were there still lots of highs despite the many challenges with such a large-scale trial?

The team in Mexico at the national cancer centre were excellent, but it was a struggle for them to find the extra finances to pay for the trial drugs and for the trial management. We were not permitted to use any grant funding to support overseas sites. Lack of financial resources is a huge barrier to academic trials worldwide, but especially in low- and middle-income countries.

It was great to get the two centres in India on board. It was their first international clinical trial. So it was necessary to guide them through the process. But it was very gratifying to see all the hard work put in by the team there.

The trial’s treatment uses drugs that have been around for years. Does this mean they’re relatively affordable, even in low- and middle-income countries?

Yes, they are both available and affordable.They’re available in most parts of the world; you can access paclitaxel and carboplatin very cheaply.

What was the highlight of the INTERLACE trial for you?

A real personal highlight was recruiting the last patient, in November 2022. I was so excited to have got the study over the finish line. The next high point was seeing the survival data. Even though I’d seen good results in my patients and hoped for a positive result, we needed to see the results from the overall analysis .

Another big high – that we didn’t anticipate – has been the huge interest we’ve had in the trial.

Am I right to assume you’ll be providing follow-up for these patients up for a number of years?

Yes, we will. The initial follow-up period was 5 years, and then we amended the protocol to allow for additional follow up: for survival beyond 5 years.

In retrospect, would you have done anything different with the study?

Perhaps try harder to convince other groups to join the trial – and then we would have completed it sooner!

Did you have much patient and public involvement throughout the trial?

We had the patients that helped us with the videos. We had a patient representative on the trial management group and she was very enthusiastic about the study.

We also put the information out there to Jo’s Trust, although the current remit of cancer charities isn’t necessarily for promoting clinical trials. I think that’s something that should change, as clinical trials are a huge part of what moves things forward for patients.

It would be helpful if relevant community groups help spread the word about research, because people trust them.

We also need to be better at getting our patients to speak about the research and their experiences as well.

So what’s next? Are you already working on the next trial?

Well, the next thing is to get the paper published! So far we’ve spent a lot of time answering queries from lots of different international research groups: there’s been lots of interest in implementing the treatment protocol across many different regions. We want to see induction chemotherapy adopted into national and international treatment guidelines.

This is the first time we’ve had 5-year survival rate figures at 80%, so it is very exciting and a bit of a new frontier for cervical cancer treatment. But I think the next step is to think of the remaining 20% that don’t benefit. For example, what role can immunotherapy play in increasing the survival rates even further? There are still plenty of questions to be answered.

In terms of getting the treatment format into treatment guidelines, what would be the next steps for achieving this?

Once published, I think the trial results would first be discussed in relation to the existing evidence that informs current guidelines.

Then, when different international guideline committees review current guidelines for possible updates, I would expect to see the INTERLACE protocol incorporated into these.

We will of course continue to publicise the results as well. With every interview and every presentation, we’re hopefully reaching an incrementally bigger audience. This will also help to crystallise the trial’s results in the existing evidence base.

It’s fascinating, and it’s such amazing work – well done for persisting with it.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorses those views or opinions.