Associate Professor Megan Smith (PhD MPH BE) is a lead researcher in the Cervical Cancer and HPV Stream at the Daffodil Centre, a joint venue between the University of Sydney and Cancer Council NSW. Her research focuses on HPV and cervical cancer prevention, including modelled policy evaluations and descriptive analyses of large datasets. She is particularly interested in optimising and successfully implementing prevention, both at the population level and in different population subgroups, considering efficiency, equity, and communications.

Megan has worked with policymakers and screening program managers in multiple countries, and is a member of multiple national or state-level committees/advisory groups related to cervical cancer prevention.

We had the pleasure of speaking with Megan to hear about current progress towards cervical cancer elimination in Australia…

What is happening around cervical cancer elimination in Australia?

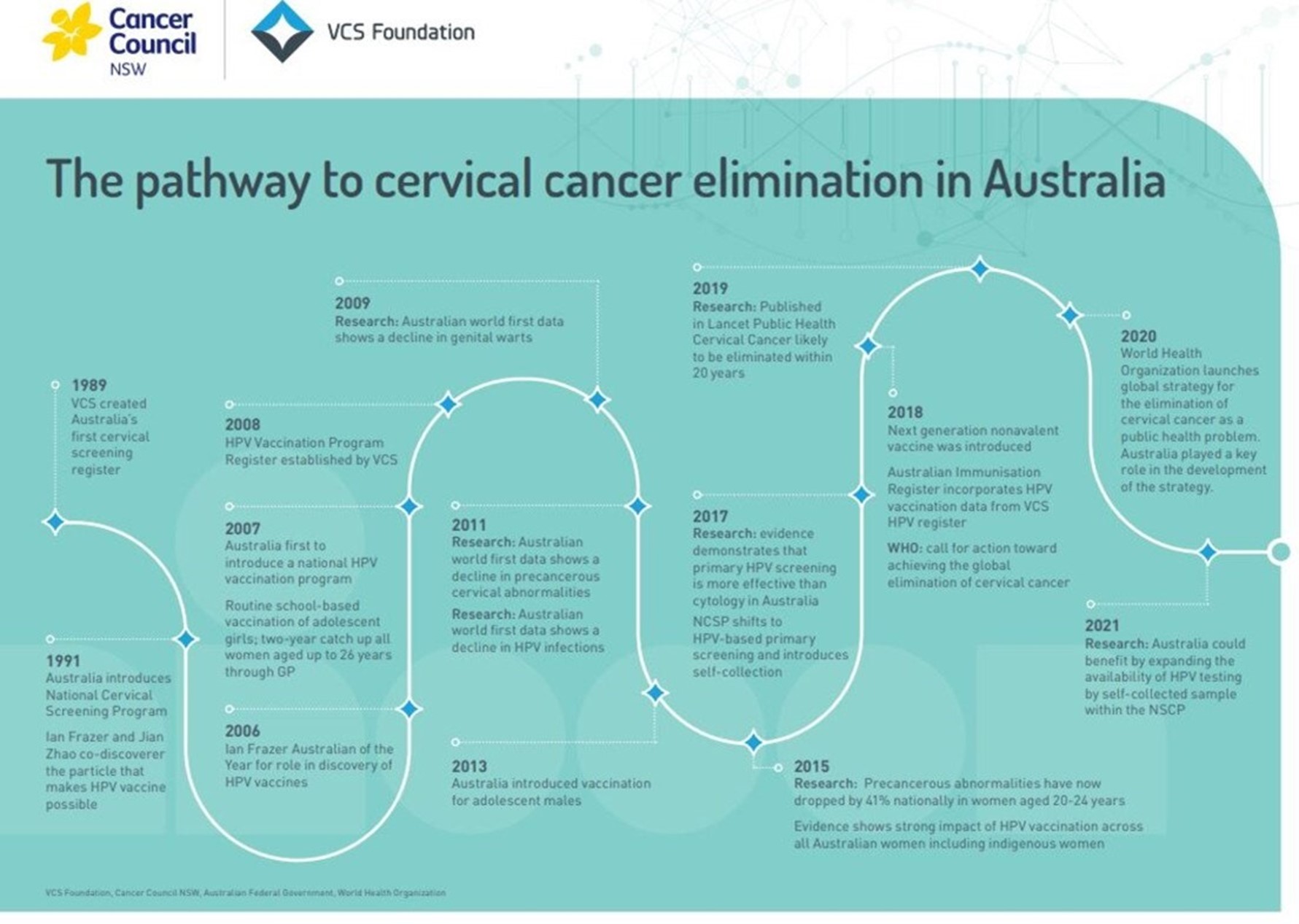

Australia is in the process of developing a national cervical cancer elimination strategy – public consultation on the draft strategy closed on 17th January and the final strategy will be released by mid-2023. Australia’s national strategy is based on the World Health Organization’s Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem but tailored for our local context.

Australia is already on a trajectory to achieve cervical cancer elimination – we have had a national HPV vaccination program since 2007 and a primary HPV screening program since December 2017. In 2021, researchers in the National Health and Medical Research Council’s Centre of Research Excellence in Cervical Cancer Control (C4) began publishing annual reports of progress against the WHO’s 90:70:90 targets for 2030, for vaccination, screening and treatment, respectively. Our most recent report has just been published and Australia is not far off meeting the targets for treatment and vaccination, given that our vaccination program also includes boys and that coverage with one dose provides strong protection. Our previous research estimated that the combined impact of Australia’s existing prevention programs could see cervical cancer incidence rates fall below the WHO threshold for cervical cancer elimination (fewer than 4 new cases per 100,000 woman-years) by around 2035.

But behind these achievements, there is substantial inequity, with some groups having much lower cervical screening rates and higher cervical cancer rates. In particular, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer and about 4 times more likely to die from it than non-Indigenous women. There are also inequities for people from some culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, those living in more remote or more disadvantaged areas, LGBTQ+ people and people living with a disability. We risk achieving cervical cancer elimination at the national level but still leaving many people suffering from preventable cervical cancer, and entrenching the existing inequities. To address this, the strategic priorities and actions outlined in Australia’s national strategy are strongly focussed on addressing current inequities, and the strategy has been developed with extensive input from priority communities. A key vision of the national strategy is for Australia’s diverse communities to have equitable access to information, and to culturally safe and inclusive vaccination, screening and treatment services. This requires a strength-based and community-led approach; recognises the importance of active partnerships; and promotes inclusivity, cultural appropriateness and a person-centred approach.

How does your work support cervical cancer elimination?

As well as being involved in developing Australia’s national elimination strategy, my work has been or is supporting cervical cancer elimination through modelling projects and policy evaluations, monitoring, and implementation projects.

Our team at the Daffodil Centre has previously undertaken modelling, predicting when cervical cancer elimination will occur in 181 countries (led by my colleague Dr Kate Simms). This has included detailed predictions for Australia and the US (the latter done with our CISNET collaborators at Harvard), with other similar work underway for Ireland and New Zealand. Our team was also one of three teams in the WHO Cervical Cancer Elimination Modelling Consortium (CCEMC) that performed modelling to support development of the WHO’s global strategy, and also assessed the impact of that strategy on incidence and mortality in 78 low- and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs). As well as predicting when elimination would occur in various countries, we’ve also identified that, while HPV vaccination is generally necessary to achieve elimination, improving or scaling up cervical screening is a key factor in determining when elimination will occur. The CCEMC also identified that scaling up cancer treatment in LMICs is the key to substantially reducing deaths in the next decade.

Given that improving access to screening is key to both expediting elimination and achieving it equitably, and that screening using self-collection provides a range of new and exciting opportunities to improve access, a lot of my work supporting elimination is focussed on self-collection. I led modelling that supported the change in Australia, from July 2022, to offer everyone eligible for cervical screening the choice of screening using a self-collected vaginal sample or a clinician-collected sample with speculum. With Dr Claire Nightingale, I am co-leading the Supporting Choice project, which aims to generate the implementation evidence needed to scale-up access to self-collection in ways that will reach and improve participation for under-screened groups, so that the policy of universal choice in Australia becomes a reality. We’ve also done modelling to support self-collection policy-making in New Zealand, and are currently collaborating with King’s Cancer Prevention Group to look at the cost-effectiveness of self-collection for under-screened women in England, using data from the King’s team’s YouScreen trial.

With collaborators in the National Health and Medical Research Council’s Centre of Research Excellence in Cervical Cancer Control (C4), I have co-led the development of an annual progress report that is monitoring Australia’s progress towards the WHO targets. Our first report was published in 2021, and our 2022 report has just been published online.

What is something that excites you about elimination / your work?

It has been exciting to be involved in developing Australia’s national elimination strategy, and to see it so strongly focussed on addressing the inequities that we have. This is clearly where Australia’s focus needs to be, because we already have a lot of good programs and treatment facilities; the problem is that they are not reaching everyone. Improving services like primary care and cancer treatment so that they are more accessible and culturally appropriate is necessary to achieve equitable elimination of cervical cancer, but it has potential benefits well beyond just cervical cancer.

I am also excited by the opportunities enabled by self-collection, to make screening more accessible and flexible. There is huge potential for innovative community-led approaches. There are two fantastic examples that are highlighted as case studies in Australia’s draft national strategy: the Prevent project, which is trialling a model of portable screening and same-day colposcopic assessment in remote areas of Western Australia; and the CheckOUT clinic, a service that was co-designed by community and clinicians to directly address barriers to cervical screening experienced by LGBTQ+ people. My hope is that we will see many other examples like this, and that successful models spread.

Finally, I’m excited by the people I work with – in my team, my collaborators, and those involved in making or delivering policy. As well as being excited by their fantastic skills and ideas, I’m excited by our shared passion to make changes to improve health and equity.

What are you inspired most by?

The prospect of eliminating a cancer, and the opportunities provided by the work required to do this to improve equity in health services and delivery more broadly.

Which failure changed you the most?

I originally trained as an electrical engineer, and I suppose I failed to be as excited as I needed to be about the details of electronics, telecommunications or computers! What I always really loved about engineering though was that it was about solving problems in the real world: solutions that had to be practical, robust and had constraints – not just ideas and theory. I think I more or less still do that, but instead applied to public health.

What is your favourite paper you’ve published in the last 5 years – the one you’re most proud of?

It was immensely exciting to have a paper published in the BMJ last year, which described the national experience in the first two years of primary human papillomavirus (HPV) cervical screening in an HPV vaccinated population in Australia, but I think the one in the last 5 years that I’m most proud of is Could HPV Testing on Self-collected Samples Be Routinely Used in an Organized Cervical Screening Program? A Modeled Analysis. This formed part of the evidence supporting the policy change to offer everyone eligible for cervical screening in Australia the choice of self-collection, a change that I think is really important to improving equity. Having a first-author paper in a high-impact journal is very exciting, but contributing to changes that I hope will improve people’s health and lives is what really matters to me.

.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.