This post is based on a longer, extended article from Lilly Matson, Cancer Research UK:

Into the Archives: the story of HPV and cervical cancer

Just over a year ago, publication of a long-awaited research study sent ripples of astonishment through the cancer research world.

Led by Head of our Group, Professor of Cancer Prevention, Peter Sasieni, the results were published in the Lancet in November 2021. They found that the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine reduced cervical cancer rates by almost 90%, in women in their 20s offered the vaccine aged 12 to 13 in England.

Even Sasieni was dubious. “My immediate reaction was that we better check this: it’s too good to be true,” he recounts.

As Cervical Cancer Prevention Week 2023 approaches, we explore in more depth how such a goal came to be realised.

Defying Reasoned Evidence: Finding the Link

As late as the 1970s, the idea of a viral-caused cancer sat wholly outside of scientific thinking. Such a model of causation remained not only overlooked but routinely dismissed. Things slowly began to change with the work of virologist Harold zur Hausen.

With interest piqued by anecdotal case reports and earlier animal cancer research, Zur Hausen and his team began investigating HPV in cervical cancer. They soon discovered multiple HPV strains. By the 1980s they had shown a strong association of HPV-16 and HPV-18 with cervical cancer, which would later see Zur Hausen jointly awarded a Nobel Prize.

With this relationship established, HPV-16 and HPV-18 were consistently found in around 70% of cervical cancer samples globally. There was now sufficient evidence to make development of an HPV vaccine possible.

Ushering in a New Paradigm of Evidence: Proving the Link

The medical community remained unconvinced by the evidence, however. They remained bound to the now outdated paradigm of scientific knowledge.

Giving a talk at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in the early 1990s, Sasieni was shocked to find the majority of clinicians doubted HPV was a cause of cervical cancer.

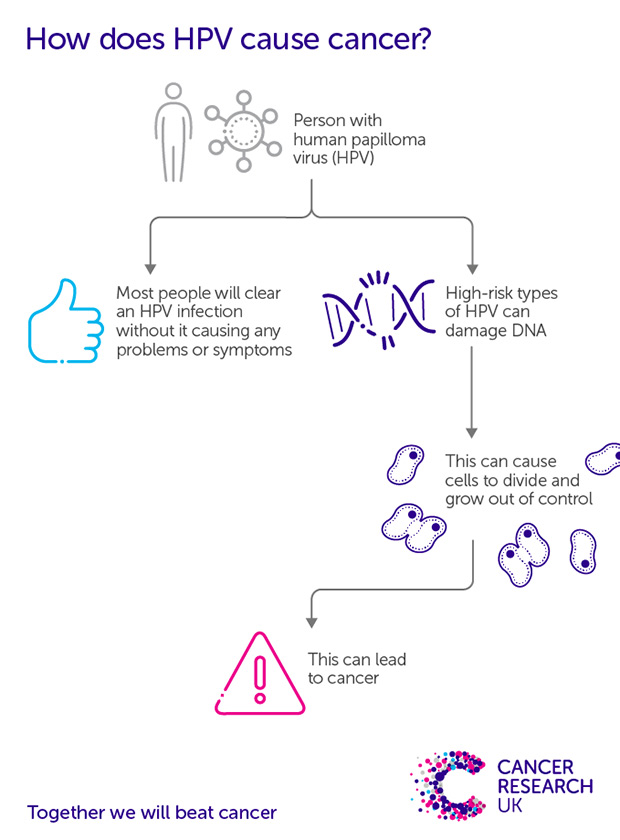

Meanwhile, the evidence continued to grow. The viral molecules responsible for uncontrolled cell growth in HPV-16 were isolated, and HPV was found in over 9 of 10 cervical cancer sample from across 22 countries. And marking perhaps the point of final confirmation, results from a study published in 1999 found HPV in 99.7% of almost 1,000 dissected global cervical cancer samples. The evidence had become undisputable.

With an evidence base both established and acknowledged, the next challenge was to create an HPV vaccine – and, with it, a hoped-for stronghold against cervical cancer.

Developing an HPV Vaccine and National Vaccination Programme Success

Most well-known for development of the HPV vaccine are Professor Ian Frazer and Dr Jian Zhou. Having initially worked together in Cambridge in 1989, they began the main bulk of their joint work in Queensland, Australia in the 1990s.

Following their work, and crucial inputs from fellow researchers, a subsequent tide of studies soon confirmed the effectiveness of HPV vaccination in preventing HPV infection. By 2006, clinical trial results had found the HPV vaccine to be 100% effective in preventing pre-cancerous lesions in the cervix. With this, the question became: does HPV vaccination reduce cases of cervical cancer?

HPV vaccination was first introduced in England in 2008: girls aged 11-13 were offered the vaccine via a schools-based programme. More recently, a catch-up programme has been introduced for women up to their 25th birthday. Boys aged 11-13, and men who have sex with men aged 18-45, are also now eligible.

Clinical trials require long, multiple-year follow-up periods for monitoring and measuring results.

While researchers on the English vaccination programme remained optimistic, they nonetheless tempered expectations with a sense of realism. But the full extent, and impact, of the programme’s success exceeded all expectations. Sasieni and colleagues demonstrated an 87% reduction in cervical cancer rates in women in their 20s, in those vaccinated aged 12 to 13.

While celebrating the possibilities of vaccine-driven prevention, researchers have remained committed to multi-pronged approaches for protection from cervical cancer. Vital in this arsenal of prevention tools is cervical screening.

Papanicalaou and Traut’s 1941 publication is frequently considered the first paper recommending cervical screening, in the form of cytological smear tests.

Cervical screening was introduced in England in 1964, but rollout lacked in organisation and quality management.

An improved, more streamlined National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme arrived in 1988. A drop in cervical cancer mortality rates swiftly followed, with the prevalence of cervical cancer in the UK halved by the end of the 1990s.

Changing the Testing Model

With an effective, efficient screening programme in place, there was fertile ground for developing the testing model further.

Screening to this point had been based on identifying any abnormal cervical cells. However, researchers knew some abnormal cells were lower risk, and capable of disappearing without any need for treatment. They set out to distinguish between high-risk and low-risk abnormal cells.

By the early 2000s, scientists had found first-line testing for HPV infection to be more effective for cervical cancer prevention than traditional cytology testing alone. But policymakers were slow to respond. The introduction of HPV pilot sites (delivering primary HPV testing) in England came as late as 2013, with primary HPV screening adoption recommended in 2016.

A 2017 paper from Sasieni stressed “the need to implement things more quickly.” It showed that a switch to primary HPV testing had the potential to prevent around 24% of current cervical cancer cases, in women invited for screening in England.

HPV screening was rolled out in Wales in 2018, England in late 2019, and Scotland in 2020.

Effectiveness of first-line HPV testing has since been further cemented, with studies supporting extended screening intervals for cervical cancer. Intervals have been increased in Wales and Scotland, with no changes to date in England.

Cervical Cancer Beyond Borders: Cervical Cancer and Global Health Equity

While there is much to celebrate, health inequities and associated challenges remain.

“Between vaccination and various forms of screening, we really do have the tools to tackle cervical cancer globally,” informs Sasieni. The World Health Organisation has created a global strategy for cervical cancer elimination. But the picture goes beyond the science.

Political will, infrastructural capacity, public trust, and close attention to the mechanisms of existing system barriers all underpin the possibility of global cervical cancer elimination. Context-specific and culturally relevant approaches are vital to achieving this.

“You can’t just say one size fits all for how you should implement this strategy worldwide,” says Sasieni.

Meanwhile, increasing evidence on a single-dose regimen of the HPV vaccine suggests comparable protection to two doses. This offers much promise for increasing HPV vaccine access globally.

Ongoing research and advocacy in low- and middle-income countries is working to increase access to, and uptake of, HPV vaccination. Self-sampling is central to this: it offers a direct tool for overcoming barriers to uptake and, with it, a means of reducing group-specific inequalities.

But capacity and infrastructure remain essential. Crucial is to “actually get the result of the test back to the person who was screened, and make the treatment available,” says Sasieni. Increasing screening capacity without necessary attention to treatment access would pose significant ethical questions.

Sasieni looks at successes to date with a steady, longer-term mindset. “To see a big reduction in cervical cancer quickly.. that means some combination of screening with vaccination,” he says. He recognises where implementation gaps can limit even the most effective of vaccines. “Vaccination is, if you like, today’s solution for tomorrow.”