This post was written by guest author Scarlett Dargan. Scarlett read History at Churchill College, Cambridge. She is now studying for a master’s in journalism at City, University of London, and working as a freelance journalist.

The story of cervical screening in England marries together science, politics, and technology. On the 23rd of October 1964, an article by John Prince appeared in the Daily Telegraph. Titled Demand grows for tests on womb cancer, it quoted the World Health Organisation’s announcement from the previous day: stating cervical cancer was now “a preventable disease.”

Mr Prince echoed the assertion “every woman from the age of 35 onwards should guard against the danger of cancer by having a cervical smear taken once a year”. With a contextually typical Cold War sway, he announced “in America and the Soviet Union, massive screening programmes are in operation. Little has been accomplished in Britain”.

As early as 1963 the incumbent Health Minister, in his annual report, “accepted routine screening for cervical cancer should be available to all women at risk.” In the following five decades, the development of England’s cervical screening programme has seen the mortality rate dive by 75%. But this programme grew out of political contention meaning the mission to “bring peace to millions of women” was often slow-moving.

Slow beginnings:

Dr George Papanicolaou discovered the potential for using cervical smears to identify early abnormalities whilst working in New York. In 1928, touched by the same element of chance as penicillin’s discovery across the pond, Dr Papanicolaou was perfecting a test to measure oestrogen activity, with planned application in aiding fertility. For years he tested on mice, injecting them with oestrogen and looking at the changes in vaginal lining, visible in smears. When the time came to test on human females, he realised he needed ‘normal’ smears to compare results post-oestrogen injection.

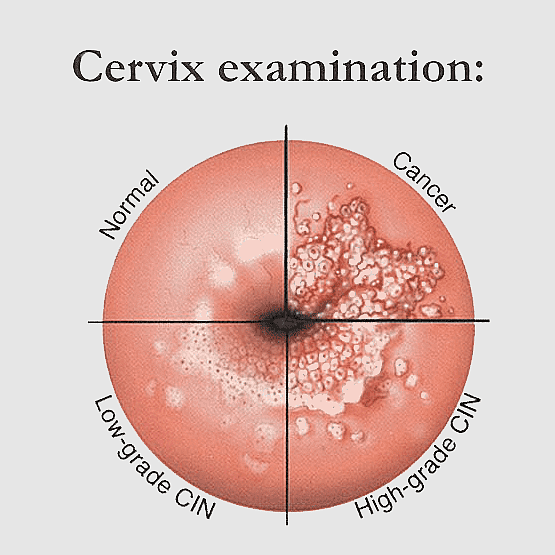

On examining these smears, Dr Papanicolaou noticed some had unusual-looking cells. Further inspection showed these abnormalities were the early incidence of cervical cancer, and thus Dr Papanicolaou discovered a remarkably straightforward method of diagnosing early disease.

Discussion over the next few decades were marked by contentions over efficacy, allegations of over-diagnosis for women with superficial lesions, and, in the early 1950s, whether gynecologists’ could even be sure of spontaneous regression of cervical cancer in situ. However, by the early-1960s, there was general medical consensus on screening’s value in detecting early abnormalities, and doctors and politicians began proposing how this pioneering test could be offered to British women.

‘The tragedy of thousands who need not die’:

In the 1950s & 60s, a mass NHS X-ray campaign and vaccination effort saw immense success in driving down Tuberculosis mortality. In reference, Lord Leatherhead stated to the House of Lords:

“If a similar mass campaign on behalf of cervical cancer were carried on in the same serious mood, we might meet with a similar degree of success… it could bring peace to millions of women; it could make many happier homes; it could save 3,000 lives a year and prevent an enormous amount of suffering.”

Pressure groups and media campaigners similarly pushed for screening; The Northern Echo from 11th June 1963 ran with the headline ‘The tragedy of thousands who need not die.’

In 1964, the Ministry of Health agreed smear tests should be offered to all women aged over at five-yearly intervals, but there was little explanation of how this would happen. A memorandum dated 13th November 1964 stated “the immediate problem is the shortage of pathologists and laboratory technicians trained in cytology. This must be overcome before routine screening for cervical cancer can be offered.” In response, the Ministry of Health funded the development of five training centres: two in London, and one in Birmingham, Newcastle and Manchester.

Despite the number of trained technicians doubling within just a year, funding for training programmes remained contentious. Minutes of a meeting held at Alexander Fleming House on 11th January 1966 saw questions raised over 283 pathologists being available for the programme – one Professor Crawford told the health minister “many of them would be employed largely in other work and would not be available to the service.”

Meanwhile, the Ministry was facing growing pressure about the lower age limit for screening. A disgruntled letter written by one advisor in February 1966 read “I think we made a mistake in accepting advice that routine screening for cervical cancer should start at 35.” Whilst “it is true that there are virtually no deaths from cervical cancer below the age of 35… carcinoma in situ can be identified in many younger women.” They concluded the age limit “will provoke outcry from women’s organisations and I think we shall be hard put to defend it.”

Meanwhile, the Ministry was facing growing pressure about the lower age limit for screening. A disgruntled letter written by one advisor in February 1966 read “I think we made a mistake in accepting advice that routine screening for cervical cancer should start at 35.” Whilst “it is true that there are virtually no deaths from cervical cancer below the age of 35… carcinoma in situ can be identified in many younger women.” They concluded the age limit “will provoke outcry from women’s organisations and I think we shall be hard put to defend it.”

Here emerged a gulf between the scientific evidence and political imperative. Whilst the Health Secretary accepted research “suggests that screening of women over 25 should pick up most early lesions” and “clearly this would be the aim of a truly preventative service”, it was decided “while facilities are limited it makes sense to concentrate on the highest risk groups.”

‘Death by Incompetence’:

These pressures meant screening was largely opportunistic with massive regional discrepancies. Regional figures collected for the Minister of Health revealed coverage for over-35s was around 50% in areas Newcastle, but as low as 8% in the South West.

An ongoing struggle was reaching women for screening, and then ensuring women, even those with normal smears, returned to be screened again five years later. Some areas developed their own systems; one cytologist working at St Thomas’ from the late-1960s remembers “we were taught from the word go to follow up with women with abnormal smears… We started a card system, always following up women.” One pioneering scheme in Aylesbury saw volunteers creating written invitation cards based on the electoral roll, which they delivered personally, encouraging women to get screened.

Whilst training centres and testing capacity increased, issues with calling and recalling women for smears and low uptake limited tangible advances. The national recall system established in 1972 was proving inefficient and cost heavy. Identifying and inviting eligible women was an arduous task based on often outdated physical records.

A ‘Cervical Cytology Report’ prepared by Health Ministry Officials in 1981 concluded “Despite the introduction in 1964 of a national schemes for screening women for the prevention and early detection of carcinoma of the uterine cervix… there has not been observed the considerable decrease in mortality from cervical cancer… achieved in some countries and regions.” There were still 2063 deaths in 1980, compared to 2068 in 1974.

These tensions were articulated in a notorious article published in The Lancet on 17 August 1985. Cancer of the Cervix: Death by Incompetence was a sophisticated criticism of the programme’s “grievously poor cost/benefit ratio”. The author looked to successful Scandinavian programmes where the death rate was plummeting to see just what was going wrong in England. The prevailing finding was administrative error – “No-one knows what proportion of women have been screened at different ages, and what proportions have not. It is not possible to find out who they are and whether they live. The responsibility for finding out is not defined.”

“The locks to effective actions were thus neither scientific nor technical, but administrative”.

The answer, for this author, was two-fold: computerisation and accountability – which will be explored further in part 2.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.

It’s important to work on preventing it.

https://lfu.edu.krd/