This post was written by Charlotte Kelley Jones. Charlotte is a postgraduate research (PGR) student within the Faculty of Life Sciences & Medicine and School of Cancer & Pharmaceutical Sciences. She works in the Cancer Behavioural Science Group within the King’s Cancer Prevention Group. Charlotte has a background in behavioural science and health psychology. Her doctoral research focuses on the acceptability of incorporating risk stratification within the NHS Breast Screening Programme.

Last Autumn, we posted a blog that outlined why the introduction of risk-stratification to the NHS Breast Screening Programme is being considered and highlighted the value of behavioural science to bridge the gap between clinical breast cancer research and implementational feasibility. Indeed, the success of a future roll-out of this novel breast screening approach will largely depend on whether women in the UK find it acceptable. The current blog reports the findings of a recent interview study by Charlotte Kelley Jones, Jo Waller (Behavioural Science Team, Cancer Prevention Group) and Suzanne Scott (Oral, Clinical & Translational Sciences) which aimed to explore women’s anticipated cognitive and emotional responses to two key stages of risk-stratified breast screening: (1) personal risk assessment and (2) risk-based breast screening.

What did the study involve?

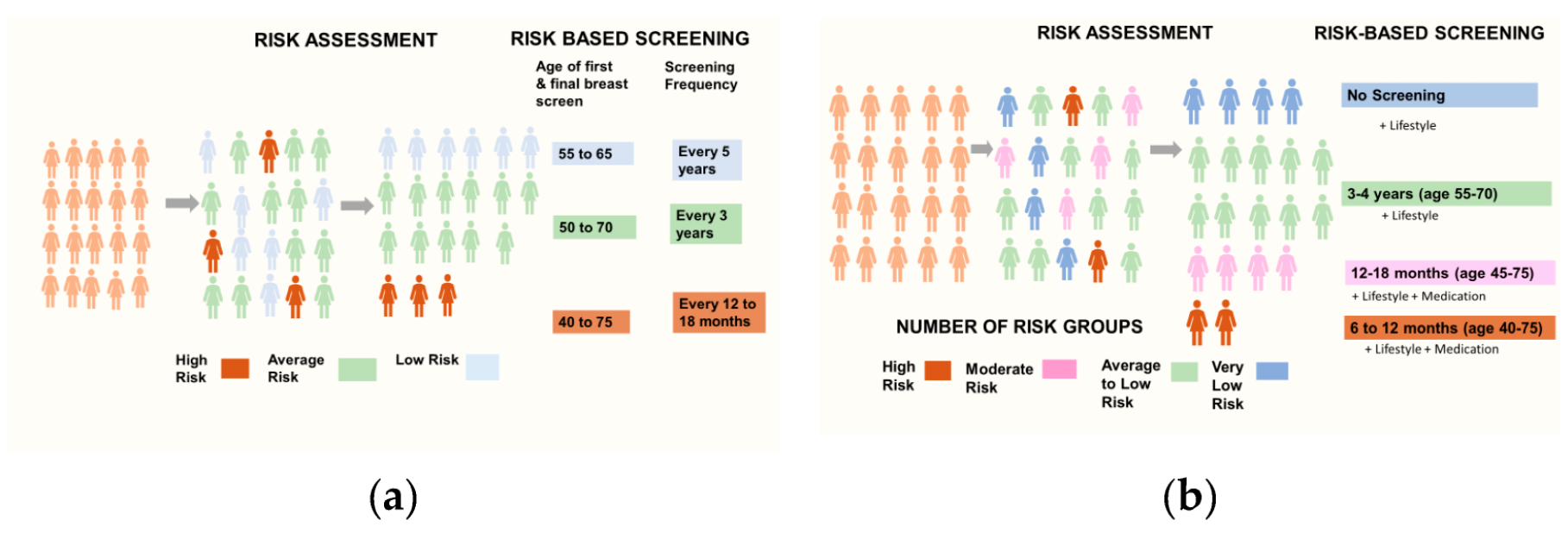

We interviewed 25 women (aged 40-69 years), with varied social backgrounds and a range of attitudes towards breast cancer and breast screening experience. The interview had two parts: Firstly, we explored women’s willingness to engage with multifactorial risk assessment, their attitudes towards the idea of combining these to compute their level of risk and their views on receiving risk-feedback. As public awareness and knowledge of breast screening varies, we gave participants a brief presentation outlining the balance of benefits and harms of the current age-based breast screening and how this may be improved by risk-stratification. During the second part, we asked participants to respond to several hypothetical, albeit realistic, risk-based breast screening scenarios. To enhance participants’ understanding, the risk-based screening scenarios were presented in steps whereby the levels for age-range of screening eligibility, length of screening intervals and risk-management options were varied with the number of risk groups.

What did we find?

In terms of multifactorial risk assessment, participants raised few concerns about undertaking measures to assess lifestyle, family, reproductive and hormonal history. Although most expressed positive intentions for having a blood or saliva swab test to determine their polygenic breast cancer risk, participants thought that women may require support to clarify the implications of the test. Most participants were unaware of breast density as a marker of breast cancer risk and the acceptability of this varied with age and breast screening preferences. Generally, these women understood and supported the rationale for combining such risk measures to compute an overall level of breast cancer risk. Some were even able to anticipate the implications of risk assessment for varying the intensity of breast screening before this was explained. Furthermore, the majority would wish to receive risk feedback as an opportunity to be pro-active in reducing their personal level of risk.

Interestingly, three distinct types of responses to risk-based screening were identified. Firstly, ‘overall acceptors’ considered most risk-based screening scenarios to be acceptable. They were united by a good understanding of the rationale for risk assessment and risk-based screening and appreciated the latter as a reasonable means of allocating NHS resources to clinical need, with some expressing a sense a relief and others able to understand this as a means of optimising the ratio of breast screening-related benefits and harms to personal level of risk. However, concerns were raised about high-risk women’s ability to cope with shorter screening intervals (e.g., 6-12 months) and some suggested that the acceptability of reducing the amount of screening for those assessed at low-risk (e.g., every five years between age 55-65) may be lower for those accustomed to regular screening.

By contrast, a second group who generally had a ‘more is better’ approach to breast screening, only considered high-risk scenarios where increased screening was proposed to be acceptable. They can be characterised by an enthusiasm for breast screening and high risk aversion and were largely resistant to information about breast screening-related harms. The third group, which, due to their ambivalent and critical attitudes to breast screening, were labelled as ‘Screening sceptics’, tended to find aspects of increased screening at higher risk problematic and unaligned with their screening values and preferences.

Sample quotes by risk-based screening response type

| Higher risk (more frequent screening over a longer period) | Lower risk (less frequent screening over a shorter period) | |

| ‘Overall Acceptors’ | “I think if you’re deemed to be at high risk …, you would want to have those additional checks and those earlier checks as well , because that’s going to be a concern if you’re high-risk and you’re going to want to do something about it. So, I think yes, definitely” (Pre-eligible, 40 years).

|

“To avoid unnecessary screening if you don’t yet need it and make it easier for the NHS to cope with those women who are at risk” (Pre-eligible, 46 years).

|

| ‘More is better’ | “ …anyone at high risk should be screened as much as possible”

(Pre-eligible, 48 years).

|

After the first year of the screen, I will worry and have to wait another four years. So that means I have to check my body more frequently myself”. (Regular attender, 68 years)

|

| ‘Screening sceptics’ | … “a shadow… that would be a difficult adjustment to make... It’s, you know, sort of not a death sentence, but you know what I mean? … it would be hard not to think negative things about that [6-12 month intervals]” (Occasional attender , 61 years).

|

“Oh, that would be good news. You know gamblers odds. But, you know, women should also have the information to say, well you’ve been judged low risk, that doesn’t mean you’re completely in the clear but just look after your health basically” (Occasional attender, 61 years). |

Overall impressions and concerns

Although the majority of participants perceived the incorporation of risk-stratification within the NHS Breast Screening Programme as clinical progress, women across all response types raised concerns and conditions of acceptability. Not least, the need for this to be effectively communicated in order for women to understand why changes are being implemented. Alongside reassurance concerning the accuracy of risk assessment, women raised concerns around how, and by whom, any changes to their risk profile would be ‘flagged’ to screening organisers in an integrated and timely manner. Others queried whether risk assessment would be voluntary and, if so, asked what happens to those who refuse this. Women expressed lack of self-efficacy in terms of how to check their breasts and know what signs of breast cancer they should look out for. Consequently, the need for breast awareness training was frequently cited as a condition of acceptability, especially for low-risk screening scenarios.

What do these findings mean and future directions?

This study provides a unique set of women’s thoughts and feelings about risk-based breast screening, and the findings are consistent with other studies in terms of high, but not universal, acceptability for this screening approach.

Although we report an overall prospective acceptability of personalised risk assessment, a woman’s age, and the timing of the tests, will be key to ensuring the acceptability of future risk assessment policy. In terms of risk-based screening, these results correspond to prior research which finds significantly higher levels of acceptability for intensified screening at high risk than for de-intensified screening for those at low risk. However, the identification of 3 different ways of responding to the scenarios presented adds more nuance in terms of: (a) the suggestion that there may be identifiable limits to how much more, or less, screening women are prepared to accept, and (b) the potential for modifying women’s attitudes to breast screening through the effective communication of breast screening-related harms. Further research is required to determine whether these types of responses to risk-based breast screening extend beyond this sample population and, if so, what are their implications for the development and testing of effective strategies for communicating risk-stratified breast screening options tailored to women’s screening values and preferences.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.