In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the current government has committed to ‘building back better’ and ‘levelling up’ communities across the UK. These slogans have generally been used in the context of improving social welfare issues – reducing deprivation, improving infrastructure, and better investment for small businesses. There’s a wealth of evidence that reducing deprivation directly correlates to improving health outcomes, something which we’ve written about in the past.

Unsurprisingly, many existing social welfare issues have been exacerbated by the pandemic; not only is COVID-19 mortality higher in poorer groups and in ethnic minorities, but life expectancy has stalled, and infant mortality and mental health problems have increased the most for those in the poorest areas.

What does building back better mean for cancer prevention and screening? With the (hopeful) focus on improving social welfare, could cancer screening and prevention also level up?

COVID-19 & Cancer

It will likely come as no surprise that, as with a lot of things, cancer screening has been impacted heavily by the pandemic. In 2020, the difficult decision was made to delay cancer screening to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19. While screening has since resumed, around 40,000 fewer people than normal started cancer treatment in the UK last year.

The exact number of excess cancers is difficult to predict. For cervical cancers, our group modelled scenarios to factor in delays, where both examples resulted in over 600 additional cervical cancer cases which may have otherwise been prevented. In a study led by Professor Kate Brain, 75% of respondents surveyed in summer 2020 said they were worried about delays to cancer tests, with follow up questions showing many worried about the potential risk of COVID-19 infection during screening appointments.

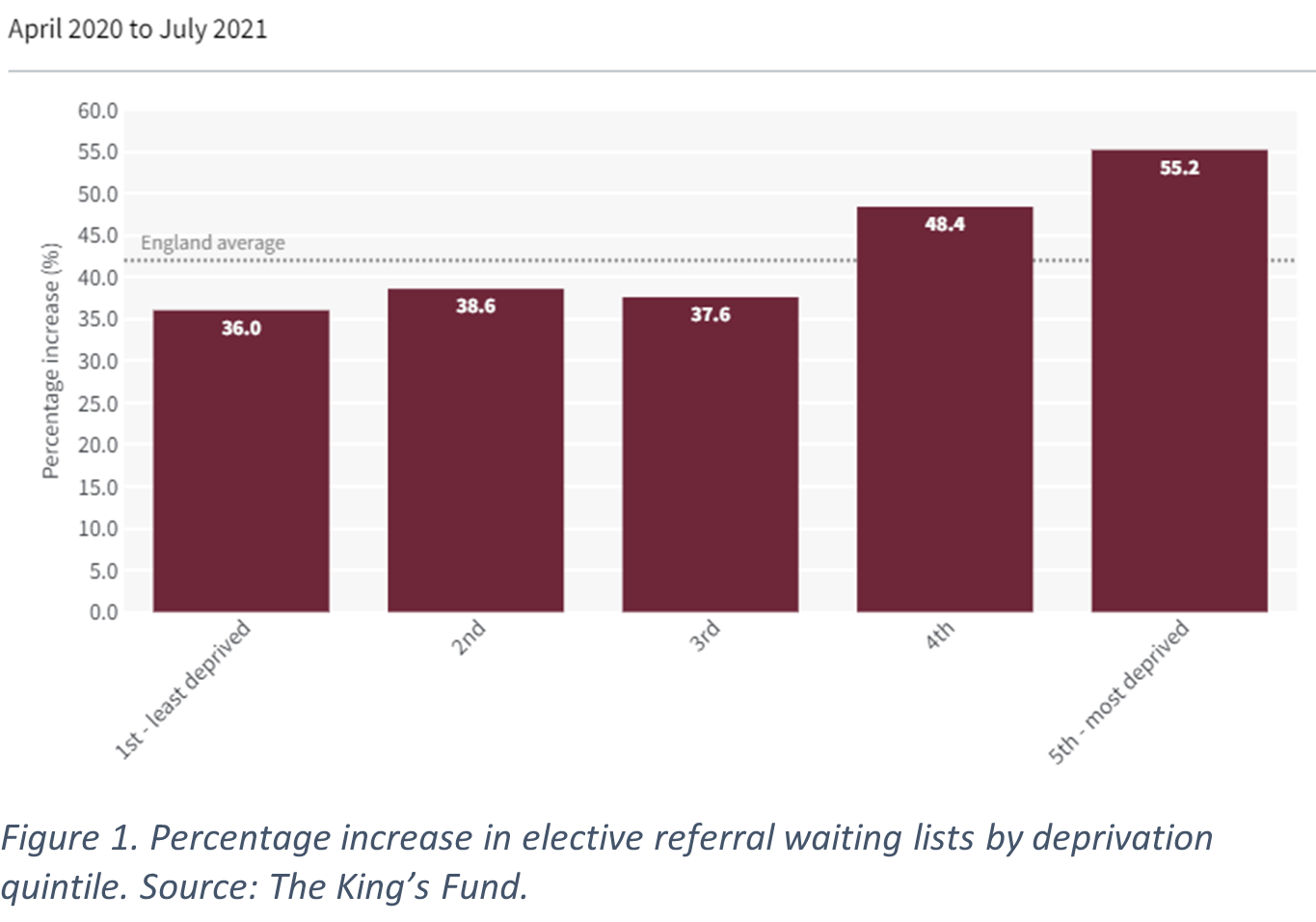

The backlog of cases – not just for cancer treatment – has a disproportionate impact upon the most deprived in England. Research shows that waiting lists in the most affluent areas of the country have increased by 35% since the beginning of the pandemic, compared with 50% for the most deprived areas. Similarly, 7% of patients in deprived areas have waited a year or more for treatment, compared with 4% for affluent areas.

Build back better

While the priority has been making sure we resume normal service to pre-COVID levels, there is also an opportunity to improve cancer screening & prevention to make it better and more effective than before.

It has long been known that socioeconomic inequalities often result in screening attendance inequalities, particularly for colorectal, but also for breast and cervical cancer. While inequalities have been improving for breast cancer, the same inequality gap has not been closing for cervical cancer, with cervical screening coverage higher in more affluent areas. New at-home screening technologies, such as those used in the YouScreen study offer a unique alternative to improve coverage and include those who may have fallen through the screening net.

Stage at diagnosis is an important indicator of overall cancer outcome. Presentation at a later stage is more common in deprived areas for almost all cancers. Trials such as NHS-Galleri offer new genomic tools to diagnose asymptomatic cancer. The Galleri test aims to find cancer earlier by detecting signals present in the blood that could indicate the presence of cancer. If the trial shows the test to be an effective screening tool, such a technology could reduce the number of late-stage cancers diagnosed.

Build back fairer

In addition, the call for evidence of the government’s 10-year cancer plan provides a perfect staging point to stamp out existing inequalities in cancer outcomes. For instance, the report mentions increasing the rollout of targeted lung cancer health checks in areas with high mortality, strongly correlated with higher deprivation quintiles. These targeted checks are shown to diagnose up to 80% of lung cancers at an early stage. Aimed at those aged 55-74 with a history of smoking, they will be placed in supermarket carparks and other easy to reach locations to reduce travel time, which can be a barrier for attendance in rural areas and particularly for those without access to personal vehicles.

Issues also exist with the delivery of cancer services. While we have previously discussed the use of remote consultations during and after the pandemic for GP appointments and referral, it is worth noting that there are substantial differences in wait time, stratified by deprivation – not just for cancer. Improvements are needed in terms of staffing to reduce these differences in wait times. Non-specific symptom pathways, highlighted in the 10-year plan aim to allow GPs to refer patients for further evaluation without the need to identify a specific cancer. Non-specific symptom pathways have been proven to be effective in diagnosing less common cancers, and reduce the need for rereferral and repeat diagnostic tests.

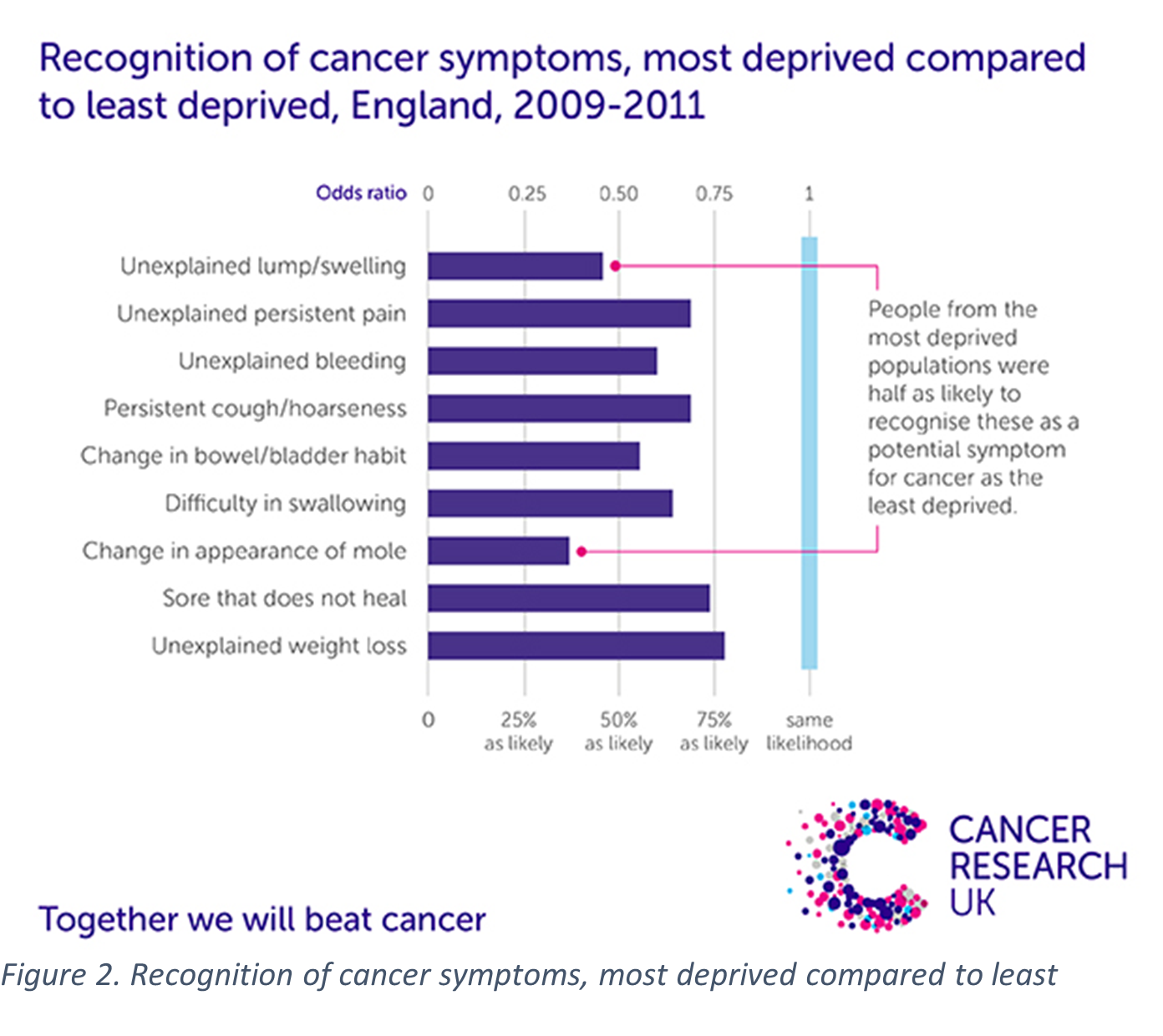

Future cancer awareness campaigns will also place an emphasis on reaching those who have cancer symptoms but did not present to health services during the pandemic, in particular, the elderly and those in more deprived areas. Research has shown that those from the most deprived areas are almost half as likely to recognise some cancer symptoms such as unexplained lumps or swelling, compared with more affluent areas. If non-specific symptom pathways are to be utilised, resources will need to be allocated towards improving the knowledge of cancer symptoms in those from deprived backgrounds.

It is hoped that this focus on increasing the proportion of cancers diagnosed at an early stage will have knock-on effects with regards to improving cancer outcomes & decreasing mortality. However, if the NHS is to reach their goal of ensuring 75% of cancer diagnoses are at stage 1 or 2 by 2028, then we cannot afford just to build back better – but crucially to build back more fairly.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.