This post was written by Rosie Brade, Senior Account Manager at MHP Communications. Rosie has previously written about her experience with vaccine hesitancy, available to read here, and how cervical cancer elimination requires collective action from civil society, which you can read here.

36% of cancer patients were concerned that remote consultations may ‘result in the wrong decision being made’ about their care. Similarly, GPs reported that remote consultations had made it more difficult to identify potential cancer symptoms than in face-to-face care – peaking at 80% of GPs when dealing with patients whose first language is not English.

Why is it that remote consultations are not integrated as part of the conversation on priority setting for earlier diagnosis?

A cause for concern?

The government are resetting their ambitions with the announcement of a 10-year cancer plan for England, due this summer. However, the call for evidence launched on 4 February does not mention the use of remote consultations in primary care at all. This is a significant omission that must be met with explicit focus and a plan ─ remote consultations are an important entry point that can swing whether we succeed at earlier diagnosis of all cancers at stages I or II by 2028, just 6 years from now.

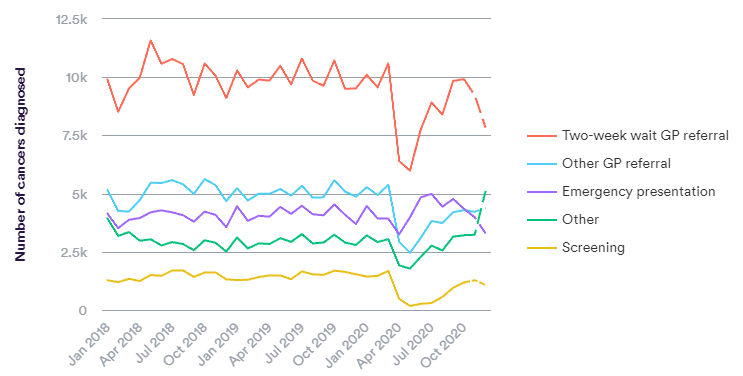

In England, most symptomatic cancers are diagnosed via primary care (via urgent and routine routes). Critically, a higher proportion of the cancers diagnosed in primary care are at an early stage, compared to emergency presentation.

What’s the current story?

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been a wealth of literature reporting the potential benefits and drawbacks of remote consultations for primary care patients. Once you get into the data, you’ll see there is a ‘but’ to pretty much every proposed benefit.

Take this example on the question of GP access ─ on the one hand, there is evidence that remote consults increase access. In a 2020 Cancer Research UK study of almost 2000 cancer patients, 58% said it was easier and safer for them to get a GP appointment since their introduction ─ people were more prepared to use remote consultations when they didn’t want to bother their busy GP. This is significant given that the top reason people were put off or delayed seeking medical help was because they found it difficult to secure an appointment. As of November 2020, 77% of GPs disagreed that patients having remote consults will always require a face-to-face appointment. This suggests that remote consults may help with triaging and reserving capacity for patients with more complex/urgent needs.

However, in this same study and as reported in several others, a ‘remote first’ approach has been criticised as an extra step with 46% of GPs agreeing that remote consultations result in multiple appointments for patients. Patients often still face delays between the remote consult and in-person appointment that ‘delays the delay’. Timely assessment and follow up remains an urgent problem and the increase in advanced presentations in A&E suggest remote consultations are not helping to fix the problem.

Two sides to the same coin

Something that continues to play on my mind, is the growing concern that remote consultations stand to disproportionately disadvantage certain groups ─ those who are already disadvantaged in cancer care. This includes older and vulnerable patients, in addition to patients who face communication barriers e.g., hearing/speech impairment, language barriers or low technology literacy. Health inequalities are at risk of becoming yet another buzzword, but it cannot be emphasised enough that the impact of remote consults on health outcomes for these groups is truly worrying.

Reaching a diagnosis is more than symptom spotting, and whilst this is known I’m not sure it’s front of mind when navigating the correct use of remote consults. The most effective consultations do this and ensure the patient is empowered to share their experience of illness, social circumstances, attitudes to risk, values and preferences ─ shared decision making.

Patient preferences and comfort matter

It is immediately obvious how virtual communication may make it harder for active engagement between the patient and GP, moving the goal post further. When it comes to smoking cessation, 40% of GPs felt that it was increasingly difficult to deliver very brief advice (VBA) via remote consultation than face-to-face. Similarly, safety netting, a consultation technique to communicate uncertainty, provide patient information on red-flag symptoms and plan for future appointments, is reportedly compromised in remote settings. 51% of GPs report patients recalling advice to be a barrier presented by telephone consultations.

In the same breath (and in keeping with their complexity), I recently undertook some research with Engine MHP where I work as a Senior Account Manager in the Health team and The Patients Association, a UK health and social care charity. We spoke to a group of patients representing a range of chronic health conditions from cancer to asthma. What we found is that for some, remote consults may help them to feel more comfortable to ask challenging questions of their GP or enable family members to join consultations and encourage positive health-seeking behaviours.

Additionally, a recent pilot study in North Tyneside found that demand and overall satisfaction for a remote platform service were highest in areas with the greatest deprivation. Such murmurings keep the flame alive that there may be a meaningful role for remote consults in all groups if used correctly. However, it may be the case that this cohort had lower baseline service expectations, so caution must be exercised to not risk papering over existing barriers.

So, it’s complicated, what next?

Cancer Research UK and Macmillan have both detailed some recommendations on best practices for remote consultations in cancer care. Here, I focus on what needs to be done from a policy perspective, when considering cancer prevention:

- A clear system view of remote consults must be adopted and national guidance for both clinicians and patients, implemented. Remote consultations must be used only for their merit and never as a proxy for face-to-face. Ultimately, guidance must be flexible to exercise patient choice and clinical judgement

- The NHS must develop specific guidance tailored to socio-economic groups and cancer types. Proportionate resource e.g., a supporting public engagement strategy, must be implemented where there is the biggest access gap and/or potential health gains from optimising remote consultations

- Patients must be involved in the design and implementation of remote consultation services. Patients from disadvantaged and vulnerable groups, and cancers of high unmet need when addressing the cancer backlog, for example, lung and urological cancers, should be proportionately represented

- The NHS should commission pathway mapping of cancer patients entering the system via remote consultation to identify motivations and barriers to presenting to a GP and how remote consultations impact on presentation and referral rates of possible cancer symptoms, diagnosis and patient experience. There is mixed data on the impact of remote consultations on the primary care interval, so further research is needed urgently

- The NHS should work with NICE to conduct a large-scale study into the impact of remote consultations on shared decision making in cancer prevention and anti-cancer treatment decisions. Industry and NHS England should commit to adapting existing shared decision-making tools for optimal use in remote settings and prioritise strategies to facilitate digital signposting to patient decision aids

The verdict? When it comes to earlier diagnosis, if used correctly ─ and this may well mean sparingly, and in highly specific cases ─ I think remote consultations can help us reach our earlier diagnosis ambitions. The catch? We must get to work now.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.