This post was written by Dr Jessica Barnes, psychologist/behavioural scientist and qualitative researcher in the Cancer Behavioural Science Group at King’s College London. She is interested in participatory research and knowledge production in the context of clinical trials, cancer prevention, and patient and public involvement (PPI).

In the previous post, we mentioned Use My Data and Understanding Patient Data as examples of efforts to bring patients’ views into the discussion about how personal healthcare data should be used. This is partly about improving transparency and ensuring that both patients and researchers understand how data can be used responsibly. These approaches recognise that there is a trust deficit between patients and researchers that needs to be addressed. However, to build trust with the public, researchers need to understand the social and political context that discussions about patient data use are embedded within, and they need to understand that building trust requires more than just making information about patient data in research available. There is a rich array of more deliberative, collective decision-making methods that can enable researchers and the public to work together to achieve what they mutually agree to be the common good.

What is the common good, and how do we (re)build a case for it?

Researchers seek to use patient data for the common good. Professor Peto alluded to a similar concept, beneficence, when he spoke of “a beneficial convention that was universally accepted from Hippocrates until my middle age,” which he appealed to as a reason why researchers should have less restricted access to patient data. The ideas of the common good and beneficence attempt to provide guiding principles for acting in ethically sound ways. However, they are more complicated than they might seem at first glance.

Researchers and theorists exploring the concept of democracy have analysed the assumptions underlying concepts such as the common good and have asked how groups of democratic citizens can discuss, agree, disagree and act on social issues. This is obviously a tradition of thought that, like Hippocrates’s beneficence, stretches back thousands of years – what does government and civic participation look like in a democratic society? However, over the past several decades, there has been a rich vein of thought that has considered different models of democratic participation that could be used in modern, liberal, democratic societies. These are models that attempt to understand whether different modes of democratic participation could allow us to reach a consensus on social issues, or whether a consensus – an agreement on what “the common good” actually is in relation to particular social issues – is even achievable, given the plurality of groups, views and values in many modern Western societies.

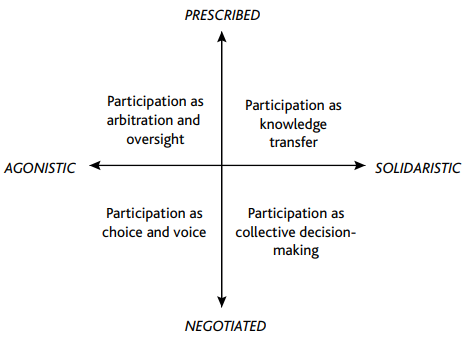

One model of democratic participation, which has become particularly pervasive under the modern neoliberal political environment, gives primacy to individual rights above a collective good. This model summarises democratic participation as giving citizens “choice and voice”. Rather than working collaboratively with other citizens to make decisions about what is morally right or in the collective interests of broader society, under the “choice and voice” model, citizens make individual choices based on their own preferences. Democracy and the common good becomes “aggregative” – it is seen as merely the aggregation of the preferences of individual citizens, rather than any collective set of broader moral values. This is the mode of democratic participation we see in proposals that individuals should have the right to choose whether their healthcare data is used in research or not.

But this is just one democratic model, and one that is based on the prioritisation of individualised choice that is part of a neoliberal society. What alternative models to democratic participation are there that could be applied in the context of patient data?

Another model frames democratic participation as “knowledge transfer” in which existing societal structures (such as government, the healthcare system, academia, etc.) invite citizens to contribute their personal experiences to the existing decision-making processes. This model can be seen in existing participatory efforts within healthcare, such as in patient and public involvement, where citizens who are potentially affected by the research are invited to contribute their opinions and experiences to the research process. In the context of patient data, this knowledge transfer model would involve researchers and policy-makers collecting public feedback and using it as one of many inputs into the decision-making process of developing an approach to patient data use that tries to reconcile multiple values and demands.

However, ultimately, the decision-making power in the knowledge transfer model lies with the professionals within the existing societal structures, which leaves it open to criticisms of not being fully participatory and inclusive. Organisational research literature demonstrates that people’s endorsement of a decision or policy that affects them depends on whether they feel their views were meaningfully incorporated into the process that produced the decision or policy. If researchers are to make the case that the public does believe that easier access to patient data for research is for a common good, they need to demonstrate that the public’s views were meaningfully incorporated into the decision-making process. Another model to democratic participation, one of collective decision-making, is a more radical and inclusive approach that could deliver this.

This collective decision-making process includes more deliberative models in which a range of people with different beliefs and values (sometimes called “mini-publics”) engage earnestly with each other with the aim of reaching a consensus on an issue. This approach offers the opportunity for in-depth, nuanced sharing of views and information, and diverse participants can potentially merge their perspectives to reach a decision that is seen as acceptable and valid. While it may not be possible to reach a full consensus amongst all participants, an inclusive, deliberative process may be the best possible way to at least converge on a shared understanding of how to tackle a social issue.

A deliberative, collective decision-making approach has been used to grapple with a variety of health research and data issues, including biobanks and population data research. These approaches revealed that, through deliberative processes, members of the public explored and developed nuanced interpretations of the issues, arriving at a deeper understanding into which their different experiences and perspectives could be integrated. It is this sort of collective, deliberative decision-making that can form a robust basis for arguments about the conditions under which researchers should be able to access patient data.

Although researchers appeal to the common good as an argument for less red tape around accessing patient data, the common good is not a monolithic, objective thing. It is collectively constructed and pluralistic, and it changes over time as the sociocultural and political landscapes change. To understand the ways in which researchers do and don’t have a public mandate to conduct research with patient data without particular oversight processes, researchers and the public need to work together and reach that understanding collectively.

What do you think? Let us know!

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.

Share this Page