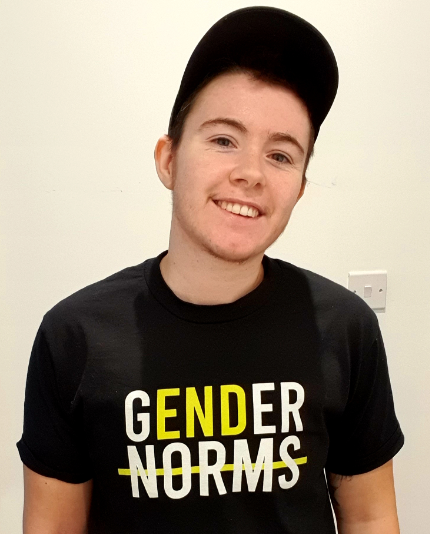

Dr Alison May Berner is a Specialist Trainee and Academic Clinical Fellow in Medical Oncology and part-time Speciality Registrar in Gender Medicine at Barts Cancer Institute. Her clinical interests include improving screening and cancer treatment for gender diverse people and the care of LGBTQ patients within oncology and the wider NHS.

It is estimated that 300,000 people in the UK identify as transgender. This population experience persistent inequalities in healthcare and screening is no exception. Trans men and non-binary people assigned female at birth in the UK are recommended to follow the same cervical cancer screening guidance as for cisgender women unless they have had surgery to remove the cervix. However, there are multiple barriers which result in both lower rates of cervical screening.

Lack of recognition by NHS systems

While NHS IT systems allow you to change your registration from male to female or vice versa, they don’t differentiate between sex and gender, and they don’t allow recording of gender identity outside this binary. If a trans man re-registers as a male with their GP, he receives a new NHS number and will no longer be automatically called by the NHS call and recall system for cervical screening.

This puts the onus onto the patient to present for screening, something that is fraught with other challenges. Guidelines transfer the responsibility to the GP (or in some cases, specialised sexual health clinics) rather than the NHS screening service, for return of results, referral and recall, increasing the risk of errors. The GP often has to call the laboratory in advance, to ensure a sample is not rejected for having a male name.

This lack of trans status monitoring is not only a problem for the individual patient. It also means we don’t have accurate UK data on screening rates. US studies indicate that the percentage of trans men and non-binary people up-to-date with cervical screening is around 10-15% lower than for cisgender women and they are 11x more likely to have an inadequate sample. In addition, our figures on screening uptake for cisgender women will consistently be inaccurate, as trans women (who do not have a cervix and do not need screening) will be recorded as not attending.

Other barriers to cervical cancer screening

A recent literature review has explored additional barriers to cervical cancer screening in a UK context. These include:

- Gender dysphoria

- Effects of testosterone therapy

- Lack of expertise in healthcare

- Lack of trans-specific information resources

Gender dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is the discomfort or distress that can be experienced when a person’s gender identity is different from their sex assigned at birth. It may be increased in a number of ways, including interaction with particular gendered body parts or by being referred to by the wrong name or pronouns.

The process of cervical screening itself may therefore be dysphoric for many trans men and non-binary people, making them less likely to attend screening. In addition, gendered invitation letters or information about screening may trigger dysphoria and result in non-attendance. However, it is important not to make assumptions about dysphoria. Some trans men and non-binary people do not experience genital dysphoria or experience it in only certain situations.

Testosterone and cervical screening

Many trans men and some non-binary people take testosterone in order to induce masculinising changes and reduce their dysphoria. This can result in vaginal atrophy, where the vagina narrows and loses its stretch, making it hard to insert a speculum to take a cervical screening sample. This may result in increased discomfort such that the person cannot tolerate the procedure long enough for an adequate sample to be taken. In addition, there is evidence that testosterone may also result in changes to the cells of the cervix, that mean results of cervical cytology are harder to interpret.

Healthcare providers can make all the difference

Awareness of these potential barriers by healthcare providers supports transgender patients to make informed choices around cervical cancer screening. Even more crucial, is the knowledge that trans men and non-binary people are at risk of cervical cancer. Many providers wrongly make assumptions about the type of sex people have and their resulting risk of high-risk HPV, the virus causing 99% of cervical cancer. Further, they assume that because someone is a trans man, they will want a hysterectomy (surgery to remove the uterus and, in most cases, the cervix) which is not the case.

Providers who are able to discuss screening sensitively with transgender patients, and adapt their technique to reduce discomfort and dysphoria, can act as facilitators for screening. These may be well-informed general practitioners, or trans specific sexual health clinics, of which there are several in the UK.

Screening information for trans people

Trans people themselves are too often relied upon to educate healthcare providers about their health needs and studies have suggested that they still lack access bespoke information and guidelines on cervical screening. Both Cancer Research UK and Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust have produced bespoke screening information for trans and non-binary people, as well as their healthcare providers.

What else can we do?

A recent study by was a collaboration between Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust, the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust, and 56T, a trans-specific sexual health service, surveyed trans men and non-binary people in the UK on their attitudes to cervical screening. It highlighted many of the barriers discussed here and led to the development of Jo’s Trust information materials. It also suggested a major facilitator of screening might be the provision of self-swabs for high-risk HPV, removing the need for a speculum. This approach has been shown to be highly acceptable to this population in the US. However, this study also showed was the variability in experiences of dysphoria, and screening and recall preferences within this population.

Improving cervical screening for trans men and non-binary people cannot employ a one-size-fits-all approach. It requires improved trans status monitoring in healthcare as well as services that are co-designed and coproduced to better meets the needs of this patient group.

Additional Reading

No Barriers Cervical Screening: Cervical screening for trans men, trans masculine and non-binary- Youtube

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.