Changing burdens of disease

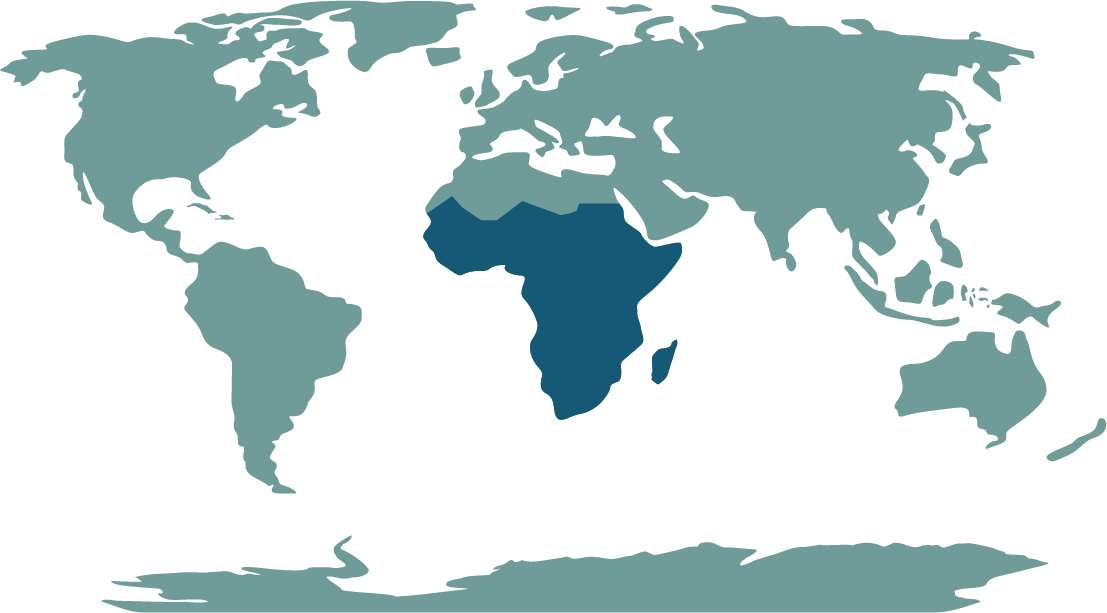

When we discuss the burden of disease in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), our mind immediately jumps to examples such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV. While mortality from these diseases are certainly high, focusing too much on these communicable diseases risks overlooking a new, worrying trend of high cervical and breast cancer rates emerging out of the SSA region. Indeed, a 2008 paper reported that over 83% of all new cases annually, and 85% of all cervical cancer deaths come from developing countries. Knowledge of the disease is low, and for those who are educated, diffusing this information into more isolated rural areas of the country is an overwhelming task.

With this in mind, what can be done to change this? What are the barriers to cervical screening for SSA?

Attitudes & issues with screening

Within the region, physical barriers such as distance and availability of screening are major factors influencing uptake in SSA. About 60-75% of all women who develop cervical cancer in SSA live in rural areas, with associated levels of very high mortality. These women often have poor access to medical facilities, attend screening too late for any intervention, or do not follow up on appointments. For those who do attend, the transportation of smear tests to laboratories for analysis presents a barrier in itself- with delays, or losses of results a significant reason as to why many women do not return to clinics for results. When an abnormal smear is identified and the result given, a referral is needed for colposcopic assessment. These are in urban-based institutions and are provided by specialists, where both distance and availability present major barriers for rural populations. Medical infrastructure in rural areas of SSA is poor, often understaffed and poorly run. The country of Malawi, with an incident rate of 47 per 10,000 women has one pathologist, one colposcope and no facilities for cervical cancer screening or treatment. Improving access and infrastructure of these clinics is essential to building effective screening relationships with local communities.

In some cases, lack of knowledge that screening exists and what it is testing is a barrier for women engagement . Conducted in 2018, a survey of women at a clinic in Lagos, Nigeria showed while 79% of attendees knew of cervical cancer, awareness of the Pap smear test was 55%- and uptake was only 23%. The most common reason for not attending a Pap smear related to a lack of knowledge or misunderstanding around the process. The idea of attending cervical screening is akin to a diagnosis of the disease. Respondents to surveys in Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda and South Africa refused to attend a Pap smear due to fear of a positive cancer diagnosis. Others in Uganda and Ethiopia saw no benefit to attending a Pap smear, as they had no gynaecologic symptoms of cervical cancer. Other women often believed it to be painful, embarrassing, or a signifier that they are unfaithful to their husbands. Stigma around HPV as a sexually transmitted disease is a common theme for those who know of the virus: where women or their husbands presume that cervical cancer is related to having multiple partners or being sexually promiscuous. This belief is intensified in communities with influential religious leaders, who are often against uptake of the HPV vaccine or cervical cancer screening.

Mechanisms exist within the SSA region for the implementation of the HPV vaccination, which is currently considered the most promising cervical cancer control strategy for this region. The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) implemented a roll out of the dual 16/18 vaccination, beginning in Rwanda- initially, the first three years of vaccination would be funded by Merck, with future doses provided at a concessional fee. Delivered through schools, the programme reached coverage of 95% of girls across the country. While the project has been successful in some countries, fear of pain and adverse effects remain barriers for adolescents and parents in Tanzania, Botswana and Mozambique. Other countries in the region implementing immunisation alongside GAVI include Lesotho, Mauritius, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa and Uganda. Key differences lie in the way Rwanda presented its immunisation campaign, working to dispel misinformation about the HPV vaccination through community partnership with local leaders, preparation of healthcare centres to facilitate demand, and a focus on schools as delivery mechanisms using multiple phases to ensure those who may have been absent are caught up. Extending the success of the Rwandan project to other countries in the region presents a major challenge in terms of socio-economic differences, as well as issues scaling the project to larger countries.

What can be done?

While SSA may seem a world away, such attitudes to cancer screening are not so different from what we have seen in the UK. Even now, stigma remains around HPV, where those who know of the disease are often misinformed as to its origins- leading to misleading titles which to this day prevent many women from attending screening. Furthermore, misunderstanding the process of cervical cancer screening has been shown to be a major barrier. Studies have shown similar sentiments to those in SSA: that screening is unnecessary unless symptoms are present, fear of a cancer diagnosis, or simply believing themselves not to be at risk. Within UK minority & faith communities, testing positive for HPV is seen as breaking trust within a marriage, being promiscuous or unfaithful.

However, successful campaigns across a variety of platforms have seen stigma and misunderstanding of HPV & cervical cancer in the UK decrease. Social media campaigns are an effective way of reaching those who have access to the internet. Coronation Street’s storyline about cervical cancer resulted in a 22% increase in smear tests in Manchester 18 years ago and more recently, another character on the show developing cervical cancer could potentially have the same impact. While not a campaign, the highly publicised nature of Jade Goody’s battle with cervical cancer led to noted increases in women attending cervical screening in March 2009. The exact mechanisms used to improve attitudes to cervical cancer screening in SSA are unlikely to be identical to those used in the UK. It is worthwhile however, to note the similarities. ‘Tinsel’ is Nigeria’s most popular soap opera, airing it’s 1000th episode in 2013- would a storyline on cervical cancer make an impact there, like it has previously in the UK?

Changes are needed in the SSA region, both in access to health facilities, and to an extent, changing attitudes to HPV and cervical cancer. Improving knowledge of HPV, and of screening is a fundamental aspect of behaviour change, but so is upgrading infrastructure to facilitate demand. Improving infrastructure and access, particularly within rural areas will almost certainly result in a decrease in rates of cervical cancer. The difficulty, however, is doing just that. In the case of Malawi, how do you improve and extrapolate the ability of one pathologist across the whole of the country, urban and rural combined? How do you begin to help those who have developed cervical cancer when no treatment facilities exist? While attitudes and behaviour may play a minor role in the increasing cervical cancer rates in the region, underlying issues of development and inequality still represent the largest barriers in SSA. Without adequate consolidation of resources, such as medical technology and education, Sub-Saharan Africa runs the risk of simply modifying its burden of disease- shifting endemic mortality in rural areas from malaria, HIV and tuberculosis to that of cervical cancer.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.

Share this Page