Dr Anita Lim tells us how her team’s research is building the evidence-base for introducing cervical screening self-testing in England, along with other approaches to make cervical screening more accessible and acceptable to women.

Fewer women than ever are coming for cervical screening in England. Attendance has hit a 21 year low with as many as 1.3 million women not attending. This is a problem because under- and un-screened women are at the highest risk of developing cervical cancer. The good news is that cervical screening is getting much easier. Self-sampling enables women to take their own test for cervical screening in the comfort of their own home. Not only is this empowering for women but it could also help address inequalities.

A ‘game-changer’ for cervical screening

Many of the reasons why women don’t come are to do with the test itself. Cervical screening (or ‘smear tests’) has always been an intimate and uncomfortable procedure carried out by a doctor or nurse. This can lead to embarrassment or fear of having a test and can make screening particularly unappealing for women with a history of abuse, past bad smear test experience or with physical disabilities or who are LBGT+. Another major barrier is around booking the appointment itself. Modern life is busy and getting appointments in GP primary care is increasingly difficult.

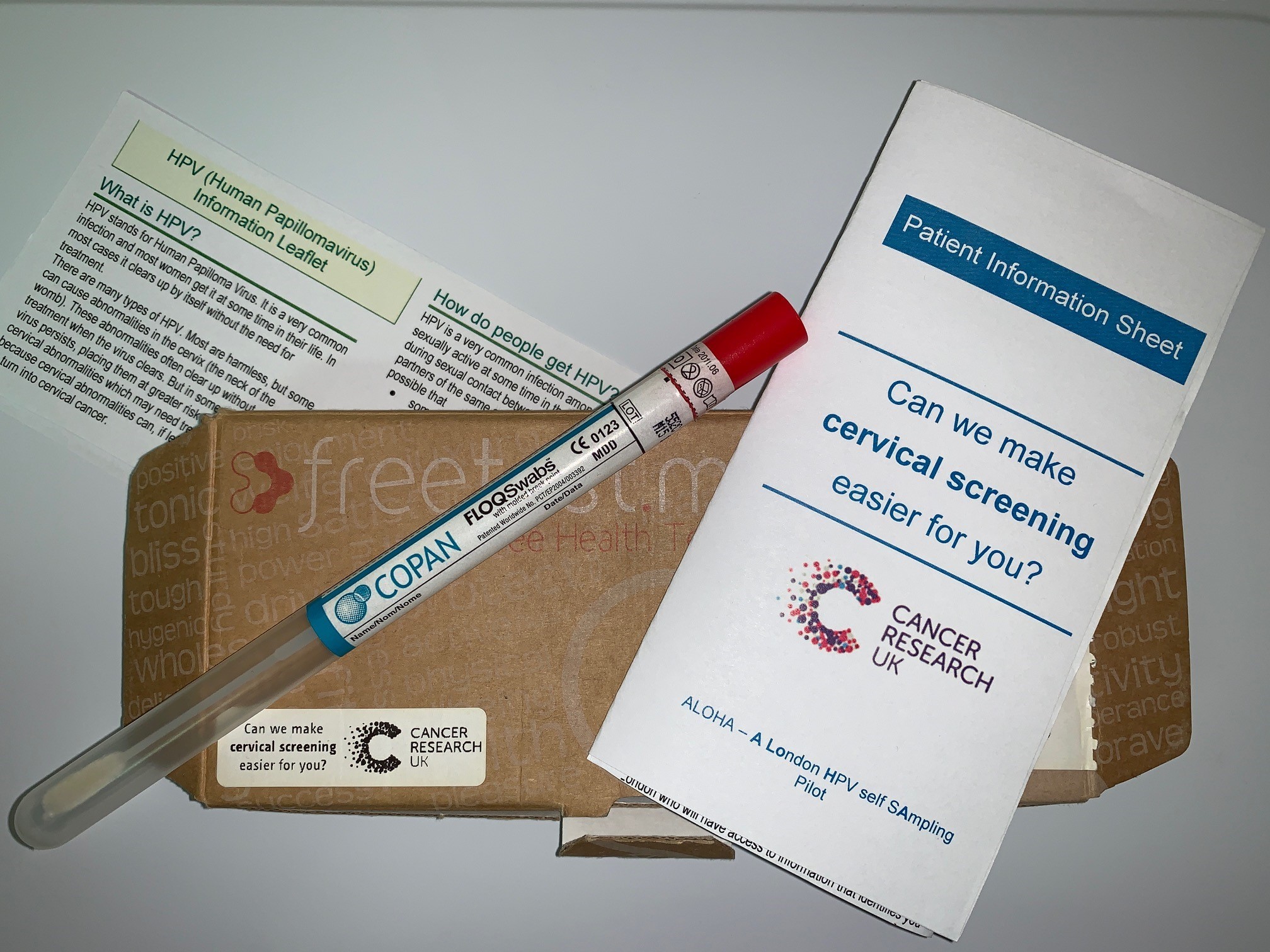

Self-sampling single-handedly breaks the barriers of embarrassment, fear, and busy lifestyles by enabling women to take a test themselves in private, at a time and place of their choosing in just a few minutes. No examination or appointment are needed and most women find it completely painless. Kits contain everything women need to collect their own sample and post it to the laboratory for analysis. The sampling device is usually a vaginal swab or brush. At the laboratory, self-samples are tested for high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) – the virus which causes cervical cancer. Studies show that self-sampling uptake is non-attenders is 20-30% and that women prefer it to clinician sampling. In short, self-sampling could be a ‘game-changer’ for cervical screening.

The next frontier

Self-sampling is already being offered to non-attenders in the national screening programmes of The Netherlands and Australia. Until recently, self-sampling has mainly been considered for women who aren’t coming for screening because the clinical performance of self-samples was not quite as good clinician samples. Last year, two key pieces of evidence emerged to challenge this. An updated meta-analysis found that self-samples are similarly accurate to clinician samples (when using HPV assays based on polymerase chain reaction). The IMPROVE trial showed for the first time that self-samples were no worse than clinician samples in a routine screening population. Both represent a major step forward in building confidence in self-sample test performance and indicate that the offer of self-sampling could be extended to all women as the primary screening method (i.e. not just those who are not coming). A very exciting prospect.

Our research group is working on several self-sampling studies. Previous UK studies found uptake to be low (6%) when kits were mailed to women. We explored the potential for offering kits opportunistically in GP primary care. Our audit of electronic GP records found that 60% of women at least 6 months overdue cervical screening consulted their GP practice over one year and that when offered kits opportunistically, 45% return a self-sample. In the ongoing ALOHA study women are either offered kits opportunistically in GP primary care when they consult for any reason, sent kits directly to their home or sent letters inviting them to order kits (online or by post). It aims to find the optimal combination of approaches for offering self-sampling kits.

We are working in partnership with the UCLH Cancer Collaborative and relevant stakeholders within the NHS and PHE, on developing an implementation feasibility project of self-sampling. This is still in the planning stage but will hopefully provide the first evidence on the impact of self-sampling on screening coverage when embedded within a national screening programme in the UK. The project is due to start in early 2020.

A speculum-free zone

A drawback of self-sampling is that women worry they haven’t taken the sample correctly. We are also exploring the potential for HPV tests taken by a doctor or nurse but without a speculum [the instrument used to hold the walls of the vagina open during smear-taking] using a vaginal swab (as with self-sampling). Having a speculum inserted can become particularly uncomfortable around the menopause. Several postmenopausal women in our study were unable to have their routine cervical screening test taken at their GP practice because inserting the speculum was too painful. Also, there are concerns about rising cervical cancer rates in older women. We hope that offering a non-speculum test will attract older women back to cervical screening who may have stopped coming since the menopause. It may particularly appeal to women who dislike the speculum but would still prefer a clinician take the sample.

Self-sampling and non-speculum clinician sampling offer great hope to screening programmes around the world that have been struggling to turnaround a longstanding downfall in attendance. Judging by the strong media response to Professor Sir Mike Richards announcement that self-sampling will be piloted in England, it can’t come soon enough.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.

Share this page

Pingback: Cervical Cancer Prevention Week – Cancer Prevention Group Blog

Pingback: How important is cervical screening for gay & bisexual women? – Cancer Prevention Group Blog