Guest blog post by: David Mesher, Public Health England

The National HPV Immunisation Programme

The National HPV Immunisation Programme was introduced in England in 2008, initially using the bivalent (HPV16/18) vaccine. Routine vaccination was offered to 12-13 year olds, almost entirely delivered at schools. A catch-up campaign for all girls up to age 18 years old was offered in the first two years of the programme (delivered at schools and primary care settings). The HPV Immunisation Programme is expected to lead to substantial declines in the incidence of cervical cancer and other HPV-related diseases. However, these declines weren’t expected to be seen until many years after the start of the programme given the long duration between HPV infection and the development of cervical cancer. A previous post on this blog describes why it is probably still too early to see the effect of HPV vaccination leading to declining trends in cervical cancer in England.

Therefore, as an earlier indicator of the impact of the National HPV Immunisation Programme, Public Health England (PHE) has compared trends in the prevalence of HPV infection over time since the start of the programme among 16-24 year old women. Our latest publication in the Journal of Infectious Diseases presented surveillance results to the end of 2016, which included samples collected from over 15,000 women.

Therefore, as an earlier indicator of the impact of the National HPV Immunisation Programme, Public Health England (PHE) has compared trends in the prevalence of HPV infection over time since the start of the programme among 16-24 year old women. Our latest publication in the Journal of Infectious Diseases presented surveillance results to the end of 2016, which included samples collected from over 15,000 women.

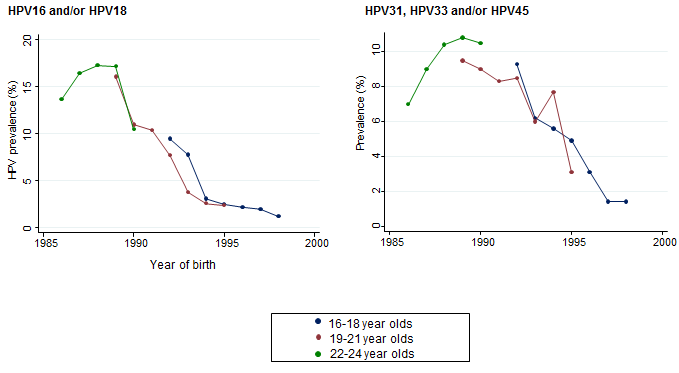

HPV vaccine-type infections reduced by an impressive 86%

The paper demonstrated that HPV 16/18 infections in women aged 16-21 (who were eligible for HPV vaccination as adolescents) decreased by 86% between 2010 and 2016. As well as seeing a significant reduction in HPV type 16 and 18 that cause around 80% of cervical cancers, the study also showed clear declines in the prevalence of HPV31, HPV33 and HPV45. These types aren’t included in the vaccine which demonstrates clear evidence of a substantial cross-protection affect against these closely related HPV types. These five high-risk HPV types combined cause around 90% of cervical cancer cases.

No evidence that other HPV types are becoming more common

A theoretical concern was that reductions in these HPV types may lead to other HPV types becoming more common. Reassuringly, the results of this surveillance do not support this theory as the prevalence of other high-risk HPV types remained relatively constant over this time period.

In a proportion of women with a known vaccination status, it was also possible to conduct two additional analyses. Firstly, we compared the prevalence of HPV infection in vaccinated women with unvaccinated women to calculate the vaccine-effectiveness. Secondly, we could look at changes in the prevalence of HPV in women known to be unvaccinated to look for evidence of a herd protection effect (where unvaccinated people are indirectly protected from HPV infection).

The vaccine-effectiveness against HPV16/18 infection was 82.0% (95% confidence interval (CI); 60.6%-91.8%) for women vaccinated <15 years old. As expected, this was lower for women vaccinated at age 15-17 years old (48.7% (95% CI; 20.8%-66.8%)) as these women may have already been infected with HPV at the time of vaccination. For HPV31/33/45 infections, the vaccine-effectiveness was 54.3% (95% CI; 8.6%-77.2%) and 36.7% (95% CI; -3.4%-61.2%) for those vaccinated <15 years old and 15-17 years old respectively.

In 16-21-year-old women, the prevalence of HPV16/18 infection in unvaccinated women reduced over time from 15.9% in 2010-2011 to 6.9% in 2014-2016. Importantly, this prevalence was lower than the prevalence of HPV16/18 infection prior to the introduction of national vaccination which suggests that a HPV vaccination programme with high-coverage is offering herd protection to unvaccinated women and, by implication, also to heterosexual men. This also highlights the importance of maintaining high vaccination rates to reduce the spread of this preventable infection.

In conclusion, these results show that within eight years of introducing the National HPV Immunisation Programme, there is a substantial reduction of infections with HPV vaccine-types and closely related HPV-types. This provides further reassurance that the high-coverage HPV vaccination programme in England will almost certainly lead to large reductions in cervical cancer in the future.

You may be interested in this related content: HPV vaccine in Scotland

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.

Pingback: Rates of cervical cancer in women aged 20-24 in England seen to double – should we be worried? – Cancer Prevention Group Blog

Pingback: Why aren’t we seeing the effect of vaccination against HPV 16/18 on cervical cancer registration in England? – Cancer Prevention Group Blog

Pingback: Cervical Cancer: The Epidemic that never was! – Cancer Prevention Group Blog

Pingback: 10 must read papers from the last year – Cancer Prevention Group Blog

Pingback: Cervical Screening Programme change in Wales: what has Cervical Screening Wales done about it? – Cancer Prevention Group Blog