Following the publication of the NELSON trial earlier this month, Dr Rintoul, University Reader in Thoracic Oncology at the University of Cambridge and Honorary Respiratory Physician at the Royal Papworth Hospital, discusses the evidence for and the remaining challenges around introducing CT screening programmes for lung cancer.

Evidence to support CT screening for lung cancer being effective has taken a major step forward with the long awaited publication in the New England Journal of Medicine of the NELSON trial. The initial presentation by Professor Harry De Koning at the IASLC World Conference on Lung Cancer in late 2018 confirmed, indeed exceeded, the findings of the 2011 US National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) which was the first study to demonstrate a survival advantage for those who had undergone screening with low dose CT.

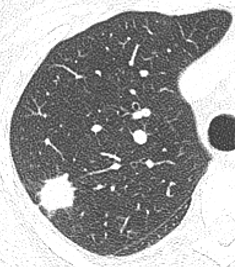

After 10 years of follow up, the Dutch-Belgian study has shown that men in the CT arm had a 24% reduction in lung cancer mortality and for women, albeit in a much smaller population, the advantage was up to 33%. Unlike its predecessor, the NELSON investigators used volumetry and volume doubling time for measuring nodule size and predicting risk of malignancy. This approach has been shown to reduce false-positive results and the need for additional investigations. NELSON also showed a stage shift. About 40% of the cancers diagnosed in the screening arm were early stage IA/B, compared with 13% in the control arm. In the control arm, 46% of cancers were stage IV at diagnosis compared with 27% in the screening arm. For many, NELSON provides the conclusive evidence that screening for lung cancer with low radiation dose CT works.

Given this new information, health care policy makers across many jurisdictions, are now faced with making decisions about implementation. Key to this is likely to be cost-effectiveness. Many factors will influence this within different health care economies including the target population, uptake rates, screen intervals, management strategies for lung nodules and implementation of effective smoking cessation services, the latter being an essential part of a successful screening programme. Within the UK, implementation studies undertaken as part of the Cancer Research UK ACE (Accelerate, Co-ordinate and Evaluate) programme along with data from the UK Lung Screening study indicate that the cost per QALY is £10-20,000, well within the limits acceptable for the UK.

In the UK, the UK National Screening Committee advises governments and the NHS about all aspects of screening and supports implementation of screening programmes. As new data becomes available it is reviewed and undoubtedly the National Screening Committee will be scrutinizing the latest NELSON results.

In the meantime, an exciting new initiative is underway. In February 2019, as part of the NHS Long term plan to diagnose three out of four cancers at an early stage, NHS England announced a programme of 10 ‘Targeted Lung Health Check’ schemes across 14 Clinical Commissioning Group areas in England. This programme is based on successful pilot schemes run in Manchester and Liverpool which demonstrated a ‘stage shift’. As seen in the NELSON study, the Manchester pilot, showed 68% of lung cancers were diagnosed at stage 1 and 11% at stage 4 compared with 18% and 48% respectively prior to the study. Rather than a national population-based screening programme, targeted lung health checks focus on individuals in a local population at highest risk for lung cancer – those aged between 55 and 75 with a history of smoking. Following the lung health check, which will involve measurements of lung function, assessment of risk for lung cancer and smoking cessation advice, those at highest risk will be offered a low radiation dose chest CT. The new programme that NHS England is investing £70 million in over 4 years will be carefully evaluated to understand the health care impacts and health economics of the programme. Many of us involved in lung cancer screening initiatives in the UK hope that this work programme will be the forerunner of a more extensive lung cancer screening programme in years to come.

In addition to evaluating implementation, the Lung Health Check programme along with other UK CT screening projects such as the Yorkshire Lung Screening Trial and the London based SUMMIT study, offer the opportunity to collect biospecimens for translational research in biomarker discovery combined with a rich radiology dataset suitable for radiomics studies.

We know from reported studies that even with deployment of risk-prediction tools to enrich for high-risk individuals, the prevalence of lung cancer in the first screening round is around 1-3%. If a way can be found to increase the prevalence of lung cancer in those targeted for CT screening, the health economic advantages will be considerable. Application of a pre-CT bench top biomarker(s) could deliver this enrichment step. Currently there are a number of on-going studies examining potential biomarkers in lung cancer but setting up large scale population-based validation studies to test promising candidates, particularly in the screening setting, is expensive and time consuming. Using an existing screening project as a biomarker test-bed would seem to be a cost-effective value added approach.

It is recognized that a lung cancer screening programme will only identify a proportion of prevalent lung cancers. There are a number of reasons for this such as selection criteria including age, as well as levels of participation and adherence. One group that is often excluded due to being deemed ‘low risk’ in current risk prediction models are never smokers, particularly women. Currently, around 15-20% of new lung cancer diagnoses in the UK are never smokers (defined as less than 100 lifetime cigarettes). This figure is gradually increasing, possibly as a result of exposure to other environmental carcinogens or second-hand cigarette smoke. Going forward, in order to identify as many cases of lung cancer as possible within any screening initiative, we will have to find new ways of identifying those at highest risk, independent of smoking status i.e. develop a personalized risk-stratified approach to screening.

While the NELSON study has done much to move forward the case for lung cancer screening, the next challenges are in terms of implementation and identification of target populations in order to optimise cost-effectiveness.

The views expressed are those of the author. Posting of the blog does not signify that the Cancer Prevention Group endorse those views or opinions.